by Andrew Wright, Associate Professor, Savannah Law School

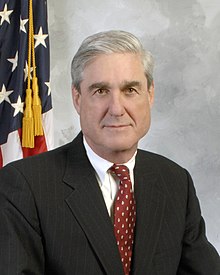

Michael Flynn is cooperating with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation. The plea agreement requires that Flynn “shall cooperate fully, truthfully, completely, and forthrightly with this Office and other Federal, state, and local law enforcement authorities identified by this Office.” Flynn’s statement of the offense ominously announces that “[t]hese facts do not constitute all of the facts known to the parties concerning the charged offense.” There is some debate about whether this agreement signals that Flynn has significant incriminating information about senior-most White House advisors, or President Trump himself. Only Flynn, Mueller, and the others whom Flynn might implicate on matters related to the investigation are in a position to know the quality of his cooperation.

But what if President Trump started using his pardon power to end the Russia investigation? What would be the effect, if any, if President Trump pardoned Flynn now? What about pardons of others that might be implicated by Flynn in his cooperation? Pardons raise a number of important questions after Flynn’s plea.

As an initial matter, a presidential pardon would relieve Flynn of punishment for the crime to which he has pled. He pled guilty to a single-count felony violation of the false statement statute, 18 U.S.C. § 1001. The plea agreement reflects an agreement by the parties as to Flynn’s estimated sentencing range under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines: 0-6 months of prison time and $500-$9,500 in fines in light of the total offense level and Flynn’s criminal history profile. A presidential pardon would relieve Flynn of all forms of punishment meted out by prison time and fines.

A full and total pardon would also erase other federal criminal exposure for any uncharged federal crimes Flynn may have committed that are within the terms of the pardon. While only Mueller has looked at all the available evidence, press reports about Flynn’s business dealings with people and entities affiliated with the Turkish government suggest Mueller, at a minimum, could have potentially sought criminal charges related to omissions and failures under the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA). The Manafort and Gates indictment demonstrates Mueller’s willingness to bring charges under FARA. Press accounts have also linked Flynn to conduct that could implicate conspiracy to commit kidnapping and criminal provisions of federal ethics laws. Flynn’s transition contacts with the Russian ambassador also raise the possibility of charges under the Logan Act because it appears he was advocating Russian actions, although that statute has its critics. In any event, uncharged crimes against Flynn, and perhaps his son Michael Flynn, Jr., remain the critical source of Mueller’s leverage to ensure Flynn’s continued cooperation. If President Trump pardoned Flynn, it would eliminate that leverage.

Presidential pardons only reach federal crimes. They have no effect on criminal prosecutions by the states. On his show The Beat, Ari Melber argued that state cooperation provision is designed to defeat presidential pardons of other parties who may have violated state law. Jed Shugerman has also advanced the theory that Mueller is playing a inside/outside federalism game as a hedge against pardons. For example, under the agreement, at the Special Counsel’s command Flynn would have to testify about any incriminating knowledge he has that would be relevant to a state money laundering prosecution against, say, Jared Kushner. The weakness in the Flynn cooperation agreement as a line of defense against the bad faith use of presidential pardons is that if the President pardons Flynn, Muller’s legal leverage over Flynn evaporates and Flynn would be less likely to honor the agreement.

While those could be significant consequences, a Flynn pardon would worsen the President’s broader legal and political troubles. It would immediately be perceived for what it was—self-protective obstruction of a criminal investigation. Some, like Andy Grewal, argue that no exercise of executive power by the President can constitute a criminal act defined by Congress. I fundamentally disagree. The use of the pardon power, like removal of the FBI director, in order to obstruct an investigation, with corrupt intent, could violate an obstruction of justice statute as well as the Take Care Clause of the Constitution. But that is a debate for another time. Self-protective pardons under these circumstances would be politically toxic, and would be an event as seismic as Comey’s firing.