October 2, 2019

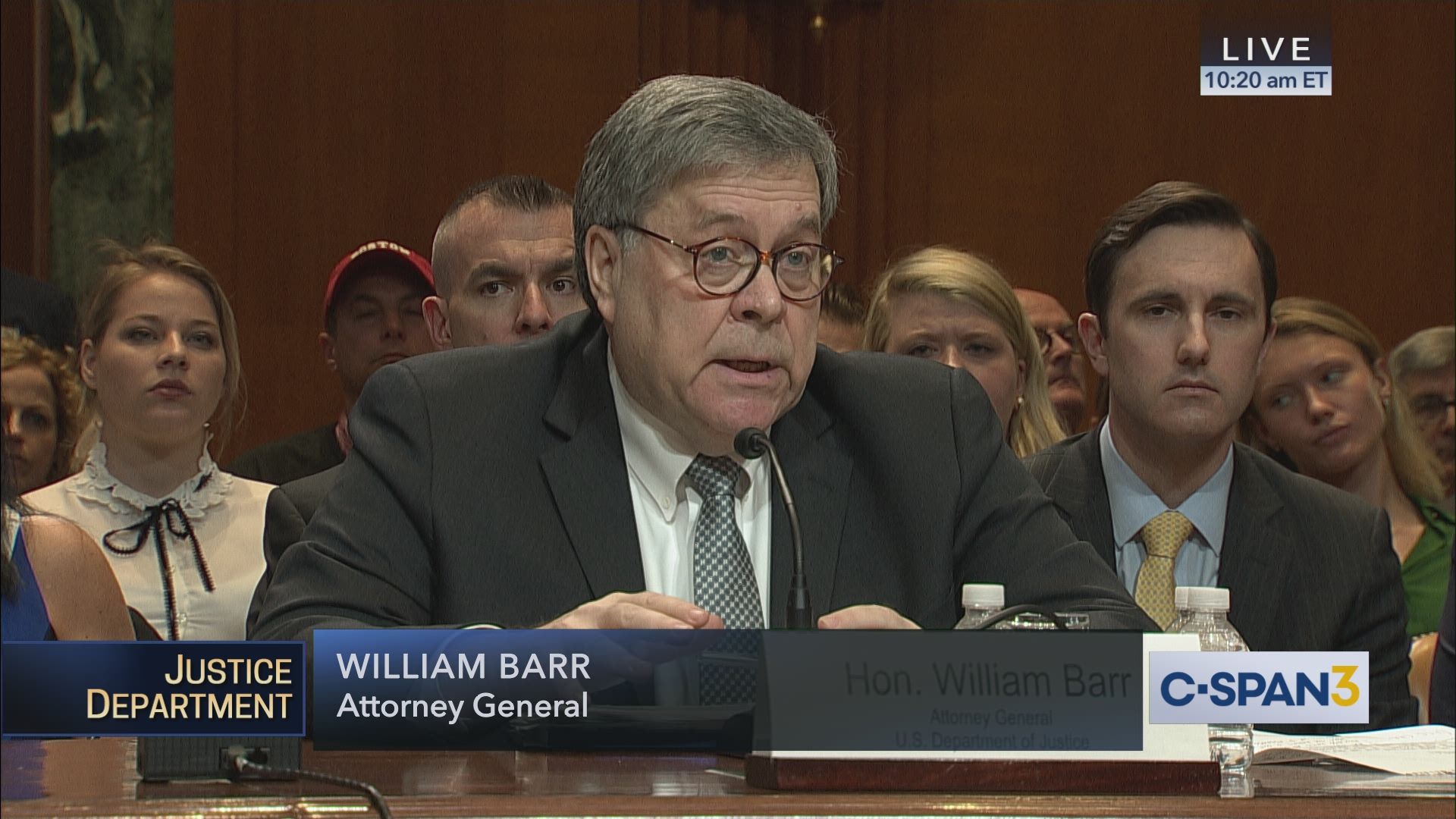

Barr Should Recuse Himself from All Things Ukraine

Professor from Practice, University of Michigan Law School, and Former U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan

This blog is one in a series of blogs in a symposium examining different legal aspects of the impeachment inquiry of President Trump. View the entire Impeachment Blog Symposium.

When I served as U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, President Barack Obama told all me and my colleagues to always remember that we did not represent him, but that we represented the American people and the Constitution. If only William Barr had heard that message.

The whistleblower complaint regarding President Donald Trump’s dealings with Ukraine raises concerns about Barr’s performance of his duties as attorney general. At the very least, by failing to recuse himself from the matter, Barr is undermining the credibility of the Department of Justice.

In August, a whistleblower filed a complaint with the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community describing a series of acts that included a July 25 telephone call between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. The whistleblower alleges facts suggesting that Trump attempted to use $391 million in U.S. military aid to Ukraine as leverage to get Zelensky to agree to investigate Joe Biden, a candidate to unseat Trump in the 2020 election.

During the call, Trump suggested that Zelensky work with Trump’s private attorney, Rudolph Giuliani, as well as Barr on the investigation. “I will have Mr. Giuliani give you a call, and I am also going to have Attorney General Barr call, and we will get to the bottom of it,” Trump said, according to the summary. The Department of Justice has issued a statement that Barr, in fact, did not talk to anyone in Ukraine about this matter or any other subject. Even so, the inclusion of Barr’s name in the report created a conflict that should have caused him to recuse himself from the matter.

Pursuant to the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act of 1998, the Inspector General for the Intelligence Community must investigate an internal complaint and determine whether it is credible and of “urgent concern.” IG Michael Atkinson concluded that this complaint met both requirements, and passed the complaint and his findings to the acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire. Under the statute, the DNI “shall” forward the complaint to the congressional intelligence committees upon such a finding. Instead, acting DNI Joseph Maguire went to the White House and the Department of Justice for advice about how to proceed, undermining the very purpose for whistleblower laws. In other words, the acting DNI went to the very subjects of the whistleblower’s complaints to ask if the complaint should be shared with Congress.

Despite the mandatory language of the text of the statute, DOJ determined that the law did not require disclosure of the whistleblower’s complaint to Congress. Steven Engel, the Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel at the Department of Justice, signed a legal opinion concluding that the whistleblower’s complaint need not be shared with Congress because the complaint did not meet the technical definition of “urgent concern.” He reasoned that alleged presidential misconduct in a classified telephone call is not an intelligence activity, and that the president is not a member of the intelligence community. Therefore, he concluded, the reporting requirement to Congress was not triggered. He concluded instead that the complaint should be shared with the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice to decide whether any crimes had been committed. DOJ’s Criminal Division reportedly reviewed the matter and concluded that it did not violate campaign finance laws.

This process seems wrong on a number of levels. First, it seems overly narrow to conclude that a matter that comes to a member of the intelligence community in the course of performing his official duties does not constitute an intelligence activity, or that the president, who has the power to classify and declassify information, is not a member of the intelligence community. Second, even if one were to agree with Engel’s analysis, the law does not permit the DOJ to second guess the IG. The language of the statute assigns the decision to the IG. Upon his conclusion of the complaint’s credibility and urgent concern, the requirement to disclose it to Congress is mandatory. Third, in light of the DOJ policy that a sitting president cannot be charged with a crime, as we learned from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, framing this matter as a criminal investigation is futile. Instead, allegations of presidential misconduct should be framed as a potential impeachment matter, further supporting the conclusion that it must be shared with Congress. Finally, even if the matter is appropriate for consideration of criminal charges, members of the Trump administration have a conflict of interest in considering whether Trump has committed a crime, and would need to request the appointment of a special counsel.

DOJ spokeswoman Kerri Kupec has said that Barr was not involved in Engel’s decision but did not recuse himself from the matter.

Under government ethics rules, recusal is appropriate if “a reasonable person with knowledge of the relevant facts would be likely to question the employee’s impartiality in the matter.” The need for Barr to recuse here is obvious. Barr’s name is included in the report as someone that Trump said he would assign to participate in activity that could amount to campaign finance violations, bribery, extortion or conspiracy to defraud the United States in the fair administration of elections. The public need not take Barr’s blanket denial as proof that he was not involved. In addition, even if one were to give Barr the benefit of the doubt that he did not, in fact, communicate with Ukraine, the inclusion of his name in the report is potentially embarrassing, creating an incentive to keep the report from Congress so that he does not have to answer questions about his own role. Conflict of interest rules exist not only to protect against actual conflicts, but also about perceived conflicts to avoid undermining public trust. The report creates at least the perception that Barr has such an incentive. A reasonable person with knowledge of these facts would be likely to question Barr’s impartiality in this matter.

In addition, as the investigation into these allegations unfold, the Department may be required to weigh in on other issues, such as whether members of the executive branch may assert executive privilege to prevent testimony or production of documents. Barr’s involvement in such decisions would undermine public confidence in the legal arguments.

Barr’s credibility is already on thin ice after his conduct as attorney general -- his decision that Trump did not engage in obstruction of justice after Mueller declined to reach a decision but found substantial evidence that he did, his parroting of Trump’s talking points that Mueller found “no collusion,” his reference to the FBI’s investigation into Russian election interference as “spying,” his investigation of the investigators, his arguably false testimony before the House that he did not know that Mueller’s team was frustrated with his characterization of the report, despite having received a letter so stating, and his evasive response to questions from Sen. Kamala Harris about whether the White House had ever suggested initiating any investigations.

Barr likely feels tremendous pressure not to recuse himself, after witnessing the treatment Jeff Sessions endured as attorney general after recusing himself from the Russia investigation. Trump’s laments that he lacked an attorney general to protect him, and his public yearnings for his "Roy Cohn" clouds public trust of the way Trump views the office of attorney general.

Barr needs to recuse himself from the whistleblower complaint and related matters to demonstrate that his office does not exist to protect the president, but to represent the people of the United States.