June 17, 2020

Safe Policing for Safe Communities: Trump’s Non-Reformist Order

Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Faculty Research and Development, Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law

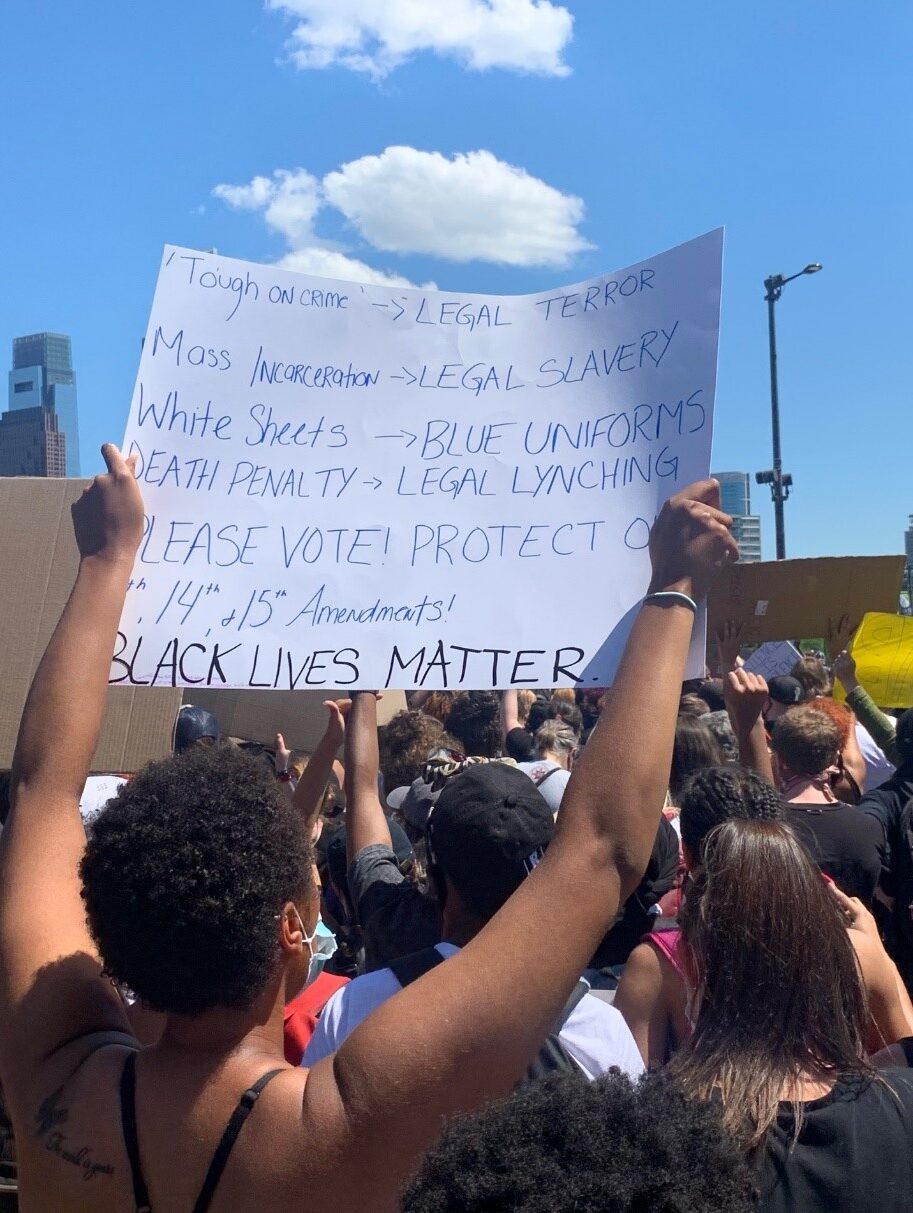

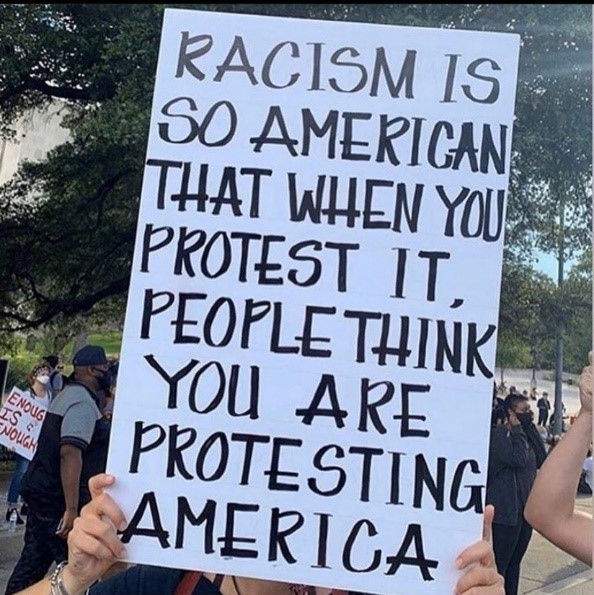

Professor Ravenell has written extensively on Civil Rights Litigation and Police Liability. She thanks Austin Skelton for his assistance with this project and credits him for the photographs included herein.

After more than three weeks of civil protests and widespread calls for police reform, President Trump finally has issued an Executive Order calling for “Safe Policing for Safe Communities.” With a perfunctory reading, one might think that the order hits many major points for reform:

- Certification and credentialing of state and local law enforcement agencies

- Databases and information sharing regarding incidents of excessive force

- Enhanced training for policing mental health, homelessness, and addiction

- Additional federal programs and funding for police.

However, a closer examination reveals that, from beginning to end, Trump’s order is light years behind the reform that activists are demanding and that state and local legislatures are considering. The order, like so many of Trump’s earlier statements, reflects an antiquated, law and order approach to policing.

The Executive Order begins with a familiar phrase: “all persons are created equal and endowed with the inalienable rights to life and liberty,” the same line that Thomas Jefferson wrote to open the Declaration of Independence. Yet, for many Americans, this phrase recalls a time when blacks were slaves and viewed as 3/5 a person. As Chief Justice Taney stated in Dred Scott, “[i]n the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.” For Trump to issue an executive order about policing in 2020, a time when protestors are chanting “Black Lives Matter,” with this particular opening phrase, is at best ignorant and at worst, another example of the race baiting that has and continues to underscore his presidency. Given his recent decision to hold his first political rally since March in Tulsa Oklahoma, the site of the Black Wall Street Massacre, on Juneteenth, a date that commemorates the end of slavery, it seems that between ignorance and race baiting, it’s more likely the latter. (Fortunately, Trump moved the rally to the next day, still in Tulsa, after his “African American friends and supporters” “reached out to suggest that [he] consider changing the date.”)

The title of the order itself, “Safe Policing for Safe Communities” reflects the idea that police are necessary to keep communities safe. Yet, a recent Vice article offers strong evidence that police are not a prerequisite for a safe community and, may actually expose some community members to unnecessary dangers. The article details how some cities have assigned traditional police duties to other professionals. For example, Eugene, Oregon’s CAHOOTS program sends specially trained teams to answer certain calls traditionally assigned to the police, like homeless, intoxication, and mental illness. Rayshard Brooks, a black man who was killed in Atlanta after a 911 call reporting that he was sleeping in a Wendy’s drive-thru, exemplifies the danger of “routine” police interactions. Police officers shot Brooks in the back three times, killing him, after he fled with one of the officer’s tasers. To be clear, the solution is to call the authorities. But systematic police reform requires that we imagine authority beyond police. Had an unarmed interventionist, like CAHOOTS, arrived and escorted Brooks home, he, in all likelihood, would still be alive. As Atlanta’s mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms observed following Brooks’ killing, “there has been a disconnect with what our expectations are and should be, as it relates to interactions with our officers and the communities in which they are entrusted to protect.” Trump’s Executive Order starts from a point upon which many disagree –that police make our communities safer.

The title of the order itself, “Safe Policing for Safe Communities” reflects the idea that police are necessary to keep communities safe. Yet, a recent Vice article offers strong evidence that police are not a prerequisite for a safe community and, may actually expose some community members to unnecessary dangers. The article details how some cities have assigned traditional police duties to other professionals. For example, Eugene, Oregon’s CAHOOTS program sends specially trained teams to answer certain calls traditionally assigned to the police, like homeless, intoxication, and mental illness. Rayshard Brooks, a black man who was killed in Atlanta after a 911 call reporting that he was sleeping in a Wendy’s drive-thru, exemplifies the danger of “routine” police interactions. Police officers shot Brooks in the back three times, killing him, after he fled with one of the officer’s tasers. To be clear, the solution is to call the authorities. But systematic police reform requires that we imagine authority beyond police. Had an unarmed interventionist, like CAHOOTS, arrived and escorted Brooks home, he, in all likelihood, would still be alive. As Atlanta’s mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms observed following Brooks’ killing, “there has been a disconnect with what our expectations are and should be, as it relates to interactions with our officers and the communities in which they are entrusted to protect.” Trump’s Executive Order starts from a point upon which many disagree –that police make our communities safer.

Rather than transferring responsibilities from over-burdened police officials to other professionals better equipped to deal with the challenges posed by mental illness, homelessness, and addiction, Trump’s Executive Order doubles down on the role of police officials. The Order does little to change the status quo. Yes, it is true that “law enforcement officers often encounter such individuals suffering from these conditions,” but this need not be the case. Emergency response systems currently assign different responsibilities to firefighters, EMTs, and police officials. It is hardly a stretch to imagine adding other professionals, like counselors and interventionists, to this system.

Cities and municipalities have looked to police officials to solve far too many problems. As Abraham Maslow observed in 1966, “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” To its credit, Trump’s Executive Order does suggest the possibility of pairing “social workers or other mental health professionals working alongside law enforcement officers so that they arrive and address situations together.” Yet, having police present in these circumstances is like taking your hammer when you all you need is your screwdriver. Progressive police reform does not depend upon the presence of police officials. It expands the toolbox.

Section 2 of the Order charges the Attorney General with allocating funding to state and local agencies that create “independent credentialing bodies.” Given what transpired in Lafayette Square on June 1, this seems particularly ironic. Not only does the Order fail to address unlawful uses of force by federal law enforcement officials (like the National Guard), but it tasks the Attorney General with overseeing this particular provision; the same official who ordered police to use force against protestors and news media in Lafayette Square. Attorney General Barr has stated, “When I came in Monday, it was clear to me that we did have to increase the perimeter on that side of Lafayette Park and push it out one block. That decision was made by me in the morning. It was communicated to all the police agencies.” Recently, more than 1,250 former Justice Department officials have petitioned for an investigation into Barr’s role. This is who is charged with police reform.

Section 5 of Trump’s Executive Order promises more funding for police to, among other things, pay for credentialing programs and retain “high-performing law enforcement officers.” This is a sharp contrast to protestors rallying cries to “defund the police.” Of course, “President @realDonald Trump stands against radical efforts to defund police departments.”

Trump introduced this Order by declaring that “the vast majority of police officers are selfless and courageous public servants. They are great men and women.” Drawing attention to “good police” is convenient because when the problem is limited to a “few bad apples” there is no need for systematic reform. This Executive Order is not systematic reform. It is hardly reform. But why does America need reform when, according to Trump, “Americans know the truth: Without police, there is chaos; without law, there is anarchy; and without safety, there is catastrophe”? Trump wants us to believe that we need police to keep us safe. He wants his base to believe that disagreeing with this statement is Unamerican. America probably needs police. America definitely needs systematic police reform. Trump’s Executive Order offers police without the reform.