April 13, 2020

Our Struggle for Rights That Others Must Respect

This piece is the forward to the 14th Edition of the Harvard Law & Policy Review.

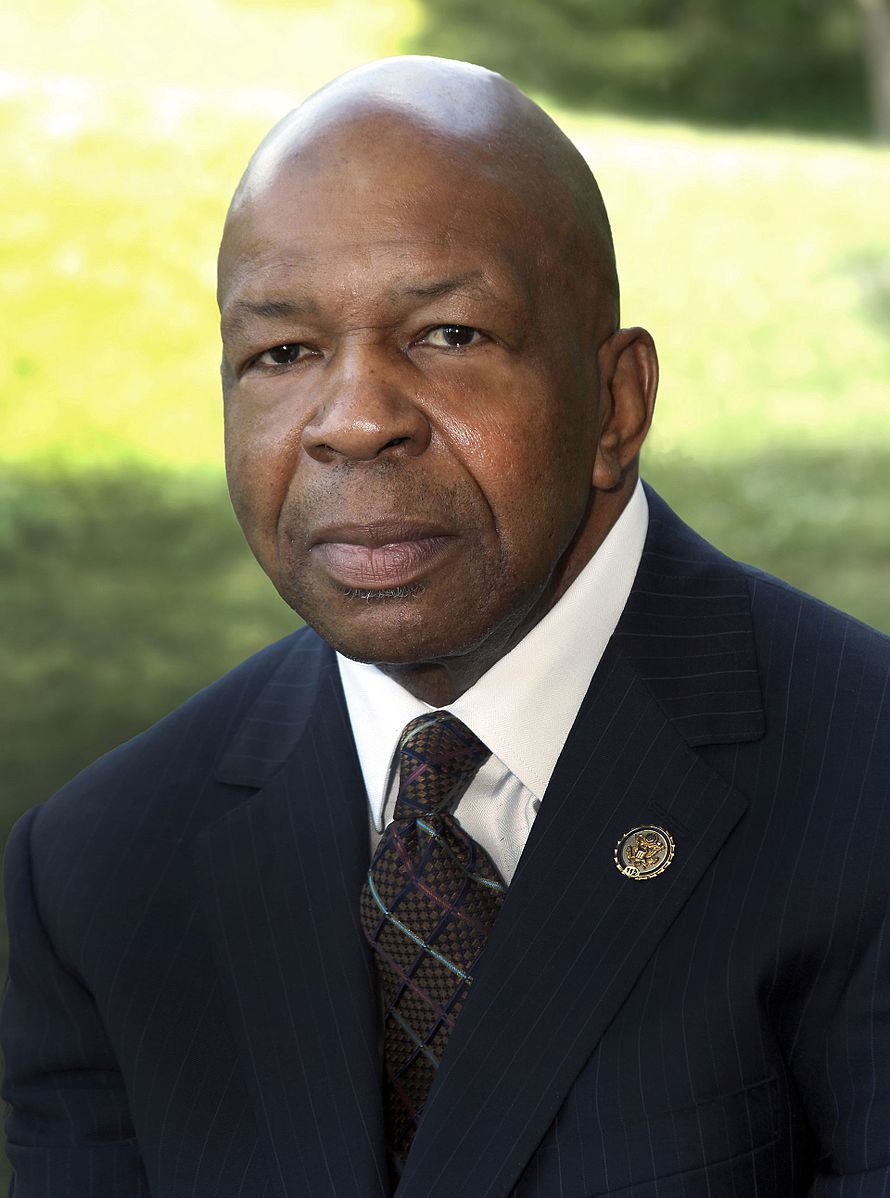

Congressman Elijah E. Cummings of Maryland

I must acknowledge that when I received the invitation to contribute a foreword to this issue of the Harvard Law & Policy Review, I experienced the mixed feelings that so often accompany challenging opportunities. In part, my ambivalence was occasioned by the very complexity of the theme— “Race in America: What has changed half a century since MLK?” The reader will find this theme broadly and ably addressed in the following pages by serious thinkers for whom I have the greatest respect. My opportunity and challenge, therefore, is to share some added value to what these experts offer.

Any assessment of the ideals, impact, and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his contemporaries within the civil rights movement of the last century will necessarily be laudatory. After all, the ideals expressed so clearly and prophetically by Dr. King were drawn from the highest ideals of justice and equality from our shared Abrahamic religious traditions, as well as (though less consistently) from the founding constitutional documents of our democratic republic. Still, a degree of humility is in order. Of equal if not greater importance, we must also recognize that Dr. King’s legacy is unfinished and, in many respects, being undone.

Progressives, including progressive lawyers, have played a role in furthering Dr. King’s legacy for everyday people in our society, including people of color. Those of us who have been privileged to be trained in the law have no exclusive, proprietary interest in the highest and most noble ideals of our society. We are less like ministers and prophets pointing the way to a nobler promised land—and more akin to engineers and mechanics, working to ap-ply the ideals of our culture and society to the practical circumstances of daily life for those who depend upon our expertise. The tools of our profession are litigation and legislation—tools that have been critical in expanding upon Dr. King’s legacy—and I have had the privilege to engage in both during the last 42 years of my professional life.

As an American of color, I have been both an advocate for the protection and expansion of our shared civil rights and, to the degree that our continuing civil rights movement has succeeded, their beneficiary. As Dr. King and the other progressives of his generation fully anticipated, the broad social, political, and economic benefits of our continuing work to perfect this democratic republic have not been limited to Americans of color. The beneficiaries have been and continue to be the hundreds of millions of Americans of every racial background, gender, and faith tradition who continue to strive for social equity and economic opportunity today, as the more comprehensive legal analyses in this edition of the Harvard Law & Policy Review will reflect.

Those benefits of the work of Dr. King and his contemporaries are limited, however, in part due to concerted efforts to roll back the very progress for which Dr. King fought. Any honest analysis of our contemporary society must recognize that the impact of Dr. King’s movement on our society and the world has been mixed—its legacy for our future left to our generation and those to come to decide.

This mixed legacy is the contemporary challenge for the lawyers and other civil rights workers of today that I have decided to address—and I will seek to do so, at least in part, from the perspective of my own life experience and that of my family. I will share these reflections and observations, there-fore, less from the perspective of a colleague who practiced law for more than 20 years and, today, as a Member of the Congress of the United States. Rather, I write to you on behalf of all the disparaged and far too often abandoned Americans of every racial background who have yet to receive the full benefits of our society.

Black Lives Matter and Trump voters alike are crying out to us for advocacy. Half a century after Dr. King gave up his life for his dream of a “Beloved Community,” millions upon millions of our countrymen and wo-men continue to be in urgent need of the protections, full citizenship, and economic inclusion that have always been the ultimate objectives of our movement for universal human and civil rights.[1] As a messenger from Dr. King’s time, I say this, to them and to you: Dr. King’s dream for America is in serious trouble. Yet, as long as there are those among us who are willing to devote our lives to moving America forward toward Dr. King’s “Beloved Community,” hope remains.

The reflections that follow advance this view in three parts:

- A reflection that describes how a former slave’s 19th century dream of full citizenship came to benefit American children of all racial backgrounds in the progressive legacy of the civil rights movement;

- An acknowledgement that, while race continues to matter in our America, the fight today to protect and expand upon the successes of the civil rights movement takes us beyond the fight against only racial discrimination; and

- A recognition that our state legislatures and the Congress must be the decisive battlegrounds in our upcoming struggles for progressive change as our courts cannot and should not be relied upon to protect and expand civil rights.

I. A PROGRESSIVE MESSAGE FROM SOMEONE WHO WAS YOUR IN DR. KING'S TIME

A. Clarendon County, SC: 1868

A Generational Dream - The Right to Vote

When Dr. King spoke of his “Dream” for America during the 1963 March on Washington, he was expressing a bedrock aspiration for my own family and millions of other Americans of color that had had its genesis nearly a century before.

Scipio Rhame was my paternal great-great-grandfather. He was a man of high expectations, even as a slave struggling to survive and thrive in Clarendon County, South Carolina. While in slavery, he was a leader in gathering other slaves together under the praying tree to have church service on Sundays. Yet, even during those difficult days, he dreamed of a better world. When he was freed from slavery, the first thing that he did was to help found the Mount Zero Missionary Baptist Church in Paxville, South Carolina. Then, he did something else that should resonate with all Americans of conscience to this day. In 1868, at the age of 50-plus years and a century before Dr. King’s murder, he registered to vote.

I thank God that my ancestor was not blinded by what he saw during the unreconstructed South Carolina of his time. I am also thankful that he dreamed of equality and meaningfully participating in our society. He dreamed this not just for himself, but for generations yet unborn. Despite the political “devil’s bargain” that prematurely ended the first Reconstruction of our nation—the Compromise of 1877—and despite the decades of Jim Crow segregation, hardship, terrorism, and poverty that followed, my own family and millions like us never completely lost faith that we would prevail in the fight for our rights.[2]

We understood, as Dr. King so often declared, that suffrage—the power of our collective voting strength in coalition with other Americans of like mind—was the foundation for advancement of all other civil and human rights. As a result of that understanding, a century and a half after Scipio Rhame’s release from slavery, his great-great-grandson, Elijah, is a Member of the Congress of the United States.

My story is possible, in large part, because a former slave from rural South Carolina, and tens of millions of other Americans of every race, had high expectations for our country. It happened because, generation after generation, those of us who proudly consider ourselves to be progressives stood up for Mr. Rhame’s dreams—dreams that went far beyond his own personal well-being. Perhaps most relevant to the legacy of civil rights that has been entrusted to us in this difficult time, it happened because—a century after Mr. Rhame’s act of courage—another generation exercised the full measure of their citizenship and won the right to vote for a second time.

B. South Baltimore:

1960s Civil Rights & Public Accommodations

During the era that would soon give America Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., my parents, Robert and Ruth Cummings, began their adult lives still struggling as sharecroppers in Manning, Clarendon County, South Carolina. They worked, but did not own, the same land that Scipio Rhame and his contemporaries had worked as slaves. Americans who know history well have a sense of how difficult life was in that county for people of color. We know it from the Supreme Court’s decision in Briggs v. Elliot,[3] one of the five cases that later would be decided under the shared designation: Brown v. Board of Education.[4]

Many people learn from the Briggs case and its companion cases about experiments involving black dolls and white dolls.[5] In the Briggs trial and these other cases, Dr. Kenneth Clark testified about social science experiments that asked black children to pick from among these dolls.[6] We re-member the harsh conditioning of inferiority, caused by segregation, when these children chose the white, rather than the black, dolls.

Fewer people remember that the original motivation for the Briggs litigation was the refusal of Clarendon County, South Carolina, to provide a public school bus for children who were forced to walk miles to attend their segregated school.[7] There in Clarendon County, my parents were denied their fundamental human and civil rights. They were denied a formal education, adequate health care, economic opportunity, and even the foundational right to vote for which their ancestors had risked their lives. Their futures must have seemed foreclosed on the days they were born. Yet, today, my brothers and sisters and I can thank God that my parents broke free from that dismal future.

For some historical context to my parents’ story: during World War II, A. Philip Randolph had convinced President Roosevelt (after significant effort) to integrate our nation’s defense industry.[8] That action created the prospect of decent jobs for thousands upon thousands of poor African Americans who, like my family, had been tied to the land like serfs in the Middle Ages. As a result, my father and mother could move from South Carolina to South Baltimore in order to create a better life for their children.

Even in Baltimore, I was disparaged and excluded in my youth. I was placed in special education in a poor and still-segregated South Baltimore elementary school. Nevertheless, we survived, and, eventually, we children thrived because my parents taught us to hold onto Scipio Rhame’s faith that a day would come when the good in Americans would outweigh our failings.

This Foreword is one piece of proof of this faith. From the very fact that readers are taking the time to consider these reflections, I know that the progressive audience here is an essential link in a generational chain of social and legal advocacy that has advanced the cause of civil rights over the generations. In that spirit, here is a personal insight about the value of that calling.

For me and the other black children in my South Baltimore neighborhood, we received our first personal lesson about the struggle for civil rights at a swimming pool called Riverside. In those days, the white children of our neighborhood swam and relaxed in the Olympic-sized Riverside Pool that Baltimore City maintained at public expense not far from where I lived. Yet, even in the “free state” of Maryland, black children like us were barred from Riverside by the cruelty of segregation.

We were consigned by the color of our skin to a small, aging wading pool at Sharp and Hamburg Streets, a pool that was so small that we were forced to take turns just to be able to sit in the cool water. Looking for a way to escape the summer heat of South Baltimore’s streets, we black children were upset about our exclusion from that public pool at Riverside—so, we complained to our recreation leader, Captain Jim Smith. To their everlasting credit, Captain Smith and Juanita Jackson Mitchell of the NAACP organized protest marches.

I would like to be able to write that the white families at Riverside accepted us graciously. After all, we were just little children who wanted a place to swim. Sadly, that is not what happened. We tried to gain entrance to the pool each day for over a week—and as we returned, again and again, we were spit upon, threatened, and called everything but children of God. On one of those children’s marches, I was cut by a bottle thrown from the angry crowd. Our parents became concerned for our safety, and Captain Smith requested police protection—but no help was forthcoming. It seemed as if we were alone in a hostile world.

Then, when all seemed lost, the NAACP’s Juanita Jackson Mitchell marched up the street toward our little group of children like she was the Empress of South Baltimore. With her were two reluctant, but grimly deter-mined, Baltimore City policemen. I can still see their faces in my mind. They clearly were more afraid of her anger than of the jeering, racist crowd.

Today, nearly six decades later, we can say that the Riverside pool was peaceably integrated.[9] It was, by Thurgood Marshall’s vision of a Constitution that provided equal rights for all and by Juanita Jackson Mitchell’s de-termination that all children would be treated fairly. On that hot summer day in South Baltimore, a lawyer stood up for what was right—for some little children who needed her. I recall this incident from my childhood because even as we honor Dr. King’s legacy, the “Dr. King” in my own life was a young lawyer from the NAACP, Ms. Juanita Jackson Mitchell. Ms. Mitchell was the engineer transmitting Dr. King’s vision into the reality of my life. Today, this difficult but uplifting memory speaks to the essence of our progressive vision for our nation and the world. It is at the heart of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and our continuing defense of equality and access to public accommodations.

As Eleanor Roosevelt once insightfully observed: “Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman and child seek equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination.”[10]

By recalling this childhood experience, I do not intend to imply that the integration of a swimming pool in South Baltimore changed the course of American history. But the experience did change my entire life.

There we were, about three years after Dr. King’s Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, the protest march when he demanded that this democratic nation give all Americans the right to vote.[11] At the time, I was just a child, but the idea of having “rights” sounded great to me. Today, some may find this reality difficult to comprehend, but before those marches at Riverside, I had never experienced having a right that other people had to respect. After we gained the right to swim in that public pool, I did have a right that was important to me. It was a right that others had to respect, and that realization made all the difference in the way that I viewed myself and our world.

C. Baltimore: 1960s

Access to an Empowering Public Education

The realization that I had rights that others had to respect, combined with the empowering foundation of a good public education, changed my life. I had spent my earliest years living in that small, rented South Baltimore row house near Fort McHenry, where the Star-Spangled Banner still waves. Every morning, like American school children everywhere, I recited the Pledge of Allegiance to that flag. I questioned, however, whether those inspiring words— “liberty and justice for all”—included me.

Our poorly equipped, eight-room elementary school did not have a lunchroom, an auditorium, or a gymnasium. Even more challenging, be-cause my parents had received little formal education themselves, they were not able to send me to elementary school ready to learn. So, there I was in segregated South Baltimore, trying to learn in what was then called the “third group.” Today, we would call that class “special education.”

Though public education ultimately empowered me to become the man I am today, one anecdote shows how even a single negative experience during these formative years could derail someone. One day, a school counselor asked me what I wanted to become in my life. I answered that I wanted to become like Ms. Mitchell, the lawyer who had stood up for us at the River-side Swimming Pool.

Since my school counselor was a black man himself, I thought that he would understand and encourage me. Instead, he just looked at me, a poor kid in the third group, the son of a laborer and a domestic, and he exclaimed: “You want to be a lawyer! Who do you think you are?” I was crushed, and I almost lost faith in myself that day.

Fortunately, that negative experience quickly gave way to far more positive influences in my youth. In the days and months to come, good teachers like Hollis Posey listened to my dreams. They believed in my potential and taught to my strengths—not to my limitations. In the evenings after school, the white librarians at our local branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library tutored me in the same subjects that I was working to learn during the day in the classroom. And outside of school, our local recreation leader, Captain Smith, took me under his arm; and Dr. Albert Friedman, our neighborhood pharmacist, trusted me and gave me my first job.

Together with my parents, these good, progressive Americans lifted me up by the strength of their example. They took my dream and made it their own. I kept working hard, and the day finally came when I made it out of the third group. Brown v. Board of Education’s desegregation mandate was having a hard-won impact in Baltimore,[12] and I was able to take the bus across town to study and graduate from one of Baltimore’s top academic high schools. Later, on scholarship, I would be able to earn a Phi Beta Kappa key and a law degree. Today, I have the honor and opportunity to represent a substantial part of the Baltimore metropolitan region in the Congress of the United States.

There is an important postscript to my personal story—a reflection that illustrates how our advocacy of Dr. King’s values in Mrs. Roosevelt’s “small places close to home” can have an impact in our nation’s broader public life.[13] When I first entered the Congress in 1996, I wondered what I would be able to bring to our debates about national policy. There I found myself, a working-class guy from Baltimore, facing the national public figures whom I had known only by their pictures on my television screen. I asked myself, “What do I have to contribute in this league?” Then, in a committee hearing one day, we began discussing the federal role in adequately funding special education—and some of my colleagues were questioning whether the money that we were spending was doing any good. That was the day that I asked to speak for the first time since I had entered the Congress.

“You ask what good are we are doing?” I challenged the cynics. “The vision and the support of good people like you raised me up from special education to earn a law degree—and I can tell you from my own life experience that we are doing more good with this education funding than you will ever know.” After I made that speech, everyone in our committee meeting looked at me—very, very quietly—and we approved a funding increase for special education that day.

This recollection from my own life illustrates an important truth that that will carry us far toward realizing Dr. King’s dream for our nation. We all have something important to offer to the shared good of our nation. Each and every person has insights and experiences that can help us create a better world. We all have had struggles in our lives that we can use as passports to helping others survive and thrive.

So, here is an answer to that deflating question from my childhood: “Who do you think you are?” We progressives are Americans who have come to understand something very important about our lives and the nation we love. The truly meaningful dreams in our lives always involve something more than our own advancement. They involve helping someone else. Dr. King counseled us that everyone can be great because everyone can serve. To that, we could add this: what we take from others in this world will be lost when we are gone. Yet the gifts that we pass on to others will remain long after we are gone and can uplift the world.

II. THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENTS OF OUR TIMES GOES BEYOND MATTERS OF RACE

Dr. King’s movement for universal human and civil rights lives on, and my current role as a Member of Congress, serving my community and our nation, exemplifies this unfinished work. Paradoxically, during the eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency, there were those who questioned the current relevance of the civil rights movement in our time. However, the 2016 national elections, as well as the actions and inactions by the current Administration, have reinvigorated our recognition that human and civil rights can be lost as well as gained.

This is why I have drawn upon my own life experience to illustrate that an important aspect of the civil rights legacy of Dr. King’s work—and that of so many other courageous Americans—was to teach us that, in America, we, as citizens, each have a calling to fight for the fundamental rights to equity and opportunity that others have the duty to respect.

A. The Intertwined Challenges of Race & Poverty in 2019

This preface brings me to a fundamental moral challenge that the majority of Americans who share Dr. King’s vision must still address and over-come: the interconnection of race and poverty. Today, more than five decades after Dr. King shared his “Dream for America” during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, we are still marching for both freedom and jobs. This ongoing movement has special significance for those of us who are Americans of color.

Minority school children, as a whole, are still far less likely to receive an empowering education. Minority students are more than twice as likely to have new and inexperienced teachers than white students.[14]The unemployment rate for African Americans is still nearly twice that of white Ameri-cans.[15] African Americans men are still more likely to die at a younger age than white men.[16] To this day, Americans of color are too often racially profiled in our justice system, denied equal opportunity in the workplace and business world, and redlined out of our dream of home ownership.

Race still matters in our America and in our fight against poverty. Race matters substantially more for those of us who are Americans of color than it does for others. Along with this socioeconomic and legal complexity, we must also acknowledge that African Americans have never been alone in having our fundamental human and civil rights denied. I will touch on both of these observations in turn.

In his seminal work, Disintegration, Pulitzer Prize-winning social commentator Eugene Robinson argues that “Black America” is no longer a distinct, unified economic entity, in large part through the legal and legislative efforts of progressives over the decades.[17]

Today, Robinson contrasts a “Mainstream middle-class majority,” the largest in our nation’s history, with a large, “Abandoned minority” who have less hope of escaping poverty than at any time since Reconstruction.[18] Among these sub-groups of the African American experience, Robinson further distinguishes what he terms a far smaller “Transcendent elite” with enormous wealth and power,[19] as well as a fourth sub-group of “newly Emer-gent” black Americans, including black immigrants and Americans of mixed racial backgrounds.[20]

While it is true that many people of color have seen economic success since the mid-twentieth century, it remains a fact that far too many Ameri-cans of color continue to face significant obstacles to achieving (or maintaining) Dr. King’s Dream in 2019. As Robinson acknowledges, a majority of African Americans may now be considered “middle class” in light of their educational attainment and incomes, but abundant evidence exists that de-cades of progress have not completely erased centuries of discrimination.[21]

Nevertheless, we also must acknowledge the second truth that I have noted. Americans of color, whatever our socio-economic position may be, are not alone in having our fundamental human rights denied. While far too many Americans of every racial background are being subjected to the most crippling segregation of all—the segregation from hope that is an almost inevitable result of poverty, Americans of color disproportionately face these barriers.

Most poor children in America are not black, but black children in America are disproportionately poor.[22] Most sick children in America are not black, but black children in America are disproportionately vulnerable to illness.[23] Most Americans who cannot afford health insurance are not black, but black families in America are disproportionately denied affordable and comprehensive health care.[24] Most of the children who are being denied a good education in America today are not black, but black children in America are disproportionately denied an effective and empowering education.[25]

Was he here with us in 2019, Dr. King would be the first to remind us that all of these children are our nation’s children, whatever may be the color of their skin? And we cannot fully honor Dr. King if we do not stand up and speak out about the denial of their economic human rights.

I believe, and we all must agree, that a hungry child has a human right to be fed. I believe, and we all must agree, that a homeless person has a human right to shelter. And I believe, and we all must agree, that a person who is willing and able to work has a human right to a fair and living wage in return for their labor. These convictions are all at the heart of what we, as Americans, must believe about human rights.

At the same time, we must also acknowledge that these human rights are all too often denied in our America. We now are engaged in a struggle to advance the human and civil rights of all Americans, whatever may be their faith tradition or their race. This deeper truth illustrates a calling for us all as progressive lawyers. Our mission—Dr. King’s vision transported into our own time—must be to transform what we believe to be the human rights of all Americans into civil rights protected by law.

III. RACE AND DEMOCRACY: VOTING RIGHTS AND ADVANCING DR. KING'S DREAM IN THE WAKE OF SHELBY COUNTY, HOLDER

In the years to come, this mission of our generation—to transform the human rights of all Americans into civil rights protected by law—will be conducted on as many fronts as there are challenges in the lives of everyday Americans. Ours is no abstract, philosophical quest. Rather, our challenge is to provide a political and legal foundation upon which Americans of every ethnic background can pursue the employment, education, healthcare, home ownership, independence, and human dignity that, collectively, give tangible meaning to Dr. King’s vision of a “Beloved Community.”[26]

Necessarily, the realization of that better vision begins in small places close to home, in the protection and education of our children and our compassion for those in our communities less fortunate than ourselves. Yet, we do not honor Dr. King solely (or even primarily) for being a minister of our shared values. We honor him and his contemporaries for their impact on our shared civic life. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was about the work of perfecting our country. His message to America was plain. The human rights that ennoble each of us—and bind us together as one society—must be afforded to the least favored among us or, ultimately, they will be lost to us all.

It is true that Dr. King was a fierce advocate for the tens of millions of Americans, like him, who were people of color. It is also true that he was calling upon our nation to offer far more opportunity and hope to all the Americans who, regardless of their racial background, were being disparaged and dismissed by our society.

The historical record is clear. The primary path to realizing Dr. King’s vision for our nation was political, as well as legal or even spiritual. So must our own journey remain.

In 1957, three years after Brown v. Board, Dr. King echoed the pain of millions of Americans in his “Give us the Ballot” speech at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom: “. . .[A]ll types of conniving methods are still being used to prevent Negroes from becoming registered voters. . . . And so, our most urgent request to the president of the United States and every Member of Congress is to give us the right to vote.”[27]

Then, in perhaps the most comprehensive expression of his “Dream” for America during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Dr. King responded to those who were asking him and the other advocates for universal civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?”

“[W]e cannot be satisfied,” he declared, “as long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.”[28]

These prophetic words from 1957 and 1963 are not the most recalled in our annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day speeches. Yet, half a century after Dr. King’s death, they retain a haunting relevance for the Americans of our time.

Once again, as in 1957, all types of conniving methods are being utilized to prevent American citizens from registering and voting.[29] Voter sup-pression remains a clear and present danger to the effective functioning of our democratic republic—and it must be stopped. Once again, as in 1963, we cannot be satisfied as long as any American cannot vote—or believes that he or she has no reason to vote. Once again, as in the time of my great-great grandfather in 1868 South Carolina, we must keep pushing forward to com-bat voter suppression, one person at a time.

In any democratic system, temporary electoral disappointments are in-evitable. Yet, when millions of Americans conclude that our democratic process is failing them because it is rigged, we are facing a threat to the proper functioning of our Republic that we, as legislators and citizens, must address.[30]

A. A Slim Supreme Court Majority Restricted Voting Rights

Until its June 25, 2013 decision in the Shelby County v. Holder voting rights case, the Supreme Court had respected the express constitutional authority granted to the Congress (not the Court) to enforce the Fourteenth and the Fifteenth Amendments.[31] It had been clear that voting rights legislation would be upheld against facial attacks as long as the congressional legislation was rationally related to enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment’s constitutional guarantees.

However, in its appalling assertion of judicial activism in Shelby County, a slim 5-4 Supreme Court majority all but usurped the clear constitutional power and duty of Congress to legislatively protect minority voting rights.[32] This one decision threatens to dismantle one of the main achievements of Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights movement. Consider these facts.

For Americans of color, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to our Constitution (commonly known at the “Civil War Amendments”[33]) are at the heart of American citizenship, equality, and free-dom. Each of those Amendments concludes by vesting in the Congress of the United States the “power to enforce” these guarantees of citizenship “by appropriate legislation.”[34] The explicit delegation of that power of enforcement to the Congress—and not to the Supreme Court—reflected the 19th century failures by the Supreme Court where slavery, citizenship, due process, equal protection, and suffrage were concerned. Then, and now, the power of voting was the key. It remains the essential guardian of a free, equal, and democratic society.

Since 1965, and prior to Shelby County, the Congress and five Presidents of both major political parties had acted to create or preserve our nation’s core legislative guarantee[35] that we will “ensure that the right of all citizens to vote, including the right to register to vote and cast meaningful votes, is preserved and protected as guaranteed by the Constitution.”[36]

On four occasions prior to Shelby County, the United States Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of the judgments that we in the Congress have made—including our judgment that the Section 5 “preclearance” requirements of the Voting Rights Act, which required certain jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory voting practices to seek preclearance with the Attorney General before changing their election laws, are essential to maintaining equal voting rights for all Americans.[37]

As recently as 2006, we in Congress reaffirmed our judgment that Section 5 remains vital to ensure that minority voters have free and full access to the polls in the jurisdictions affected. In so doing, we considered an extensive factual record—a record that was found to be especially significant by the lower federal courts that have reviewed the current challenge to Section 5.

As my colleague Congressman John Lewis summed it up in 2013: “We held 21 hearings, heard from more than 90 witnesses and reviewed more than 15,000 pages of evidence.”[38]

Specifically, Congress found ample evidence of voting discrimination in the jurisdictions covered in Section 5 by Section 4, including: intentional discrimination as documented by continued disparities in registration and turnout, low levels of minority elected officials, the number of Section 5 enforcement actions since 1982, the amount of Section 2 litigation and evidence of racially polarized voting.[39]

Our judgments in 2006 had proven well-founded. During the 2012 presidential election, Section 5’s preclearance process led South Carolina officials to reinterpret a photo ID law to reduce its discriminatory effect.[40] It also blocked a stringent Texas photo ID law that would have had a retrogressive effect on minority voters’ access to the ballot.[41] Likewise, litigation arising from Texas’ redistricting validated Congress’ concern that intentional racial discrimination in voting continues to pose a credible threat to the rights of minority voters.[42]

In short, the Supreme Court in Shelby County was presented with an abundant record[43] justifying the continued application of Section 5 “preclearance requirements” to Alabama and the other affected jurisdictions—clearly enough to pass muster under the Court’s “rationally related” test.

As Justice Ginsburg observed in dissent (joined by Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan): “The question this case presents is who decides whether, as currently operative, Section 5 remains justifiable, this Court, or a Congress charged with the obligation to enforce the post-Civil War Amendments ‘by appropriate legislation.’”[44]

In my view, the “conservative” majority in Shelby County no longer de-serves that appellation. These five justices engaged in the most egregious act of judicial activism since the Bush v. Gore decision[45] that decided the 2000 presidential election, this time rolling back crucial civil rights protections that people fought and died over.

Acting in the wake of 2011 redistricting plans and 2012 civil rights violations, the Shelby County majority thrust the issue of equal and universal voting rights back into the forefront of our national challenges. Long before our 2016 presidential election, advocates for fair elections that engage all Americans on equal terms decried the weakening of our protections against voter suppression occasioned by a misguided Supreme Court majority.[46]

In the 114th Congress, for example, I was honored to join Republican Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner, Democratic Congressman John Conyers, Jr., and more than 100 other legislators in co-sponsoring The Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2015,[47] legislation that would have repaired much (al-though not all) of the injury to our voting rights that the Shelby County decision has allowed.

Our proposed legislation never received an up-or-down vote in the Re-publican-dominated House; and, as a result, Republican legislatures in many states made it far more difficult for untold numbers of voters to cast their ballots in 2016 (especially the elderly, the young, and minorities).[48] In sharp contrast to the President’s assertions of widespread voter impersonation, the evidence[49] of voter suppression in Republican-dominated states is compelling—although the undemocratic methods vary.

State voter ID laws, unwarranted purging of the voter rolls, racially gerrymandered congressional districts, and consciously understaffed and under-equipped voting precincts in minority areas are just some of the more obvious methods being utilized to thwart our constitutional right to free and fair elections.[50] Taken together, these voter suppression methods do constitute a fraud—but this fraud is being committed by reactionary state legislators against the American people and our constitutional right to choose those who will govern us. It is not voter fraud.[51]

These politically motivated efforts to “rig” our elections may already have had far-reaching, destabilizing, and dangerous consequences. Journalist Nico Lang observed in the wake of the 2016 elections, “the low turnout for Clinton had little to do with her black support and everything to do with the effective campaign of voter suppression run by Republicans, one that has decimated accessible options for people of color.”[52] If Lang’s conclusion is correct, and there is substantial supporting evidence that it is, the Russian intervention that year, although significant, was not the only factor in Secretary Clinton’s loss. Voter suppression also played a major part.

Deprived of a President who takes his constitutional obligation to protect our voting rights seriously and opposed by then-Attorney General Sessions, who gutted the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division’s voting rights enforcement,[53] optimism about the future of our democracy may seem unrealistic. Nevertheless, I remain confident that our democratic system of free and fair elections is stronger than any individual or political party.

Americans who are committed to defending our democracy will simply have to work harder. I believe we will continue to have substantial support for this most patriotic of causes from the judiciary. But my ultimate confidence in our ability to defend our democratic system rests in the American people—in our determination to do what we must to uphold our ability to choose who will govern. When our neighbors are required to produce identification at their polling places, we will work together to help them get those IDs; where cynical politicians make voting more difficult on Election Day, we will bring a box lunch and wait our turn; and when the evidence shows racially-based attacks on our voting power, we will fight that suppression in our courts.

We are in a fight for the soul of our democracy—and this is a fight that we are determined to win.

As I write these words, reformers in the House of Representatives are moving forward with our planned public hearings and investigations to build the public record that will allow the Congress to comply with the (what I consider unwarranted) holding of the Supreme Court’s majority in Shelby County and restore the Voting Rights Act to full force and effect.[54] On a parallel track, we are also moving forward with the For the People Act, sponsored by my colleague and friend, Congressman John Sarbanes, that will be a major step toward giving all Americans a seat at the table.[55] This bill passed the House earlier this year with the support of every House Democrat, though without the vote of a single House Republican.[56] That, in turn, will allow our national government to better solve our most pressing problems (like reducing the cost of prescription drugs, combating climate change, and building an economy that works for all Americans).

The inter-related, three-fold objectives of our reform measures are clear:

- We must make it easier, not harder, to vote by implementing automatic voter registration, requiring early voting and vote by mail, committing Congress to reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act, and ensuring the integrity of our elections by modernizing and strengthening our voting systems and ending partisan redistricting.

- We must reform big money politics by requiring all political organizations to disclose large donors, updating political advertisement laws for the digital age, establishing a public matching system for citizen-owned elections, and revamping the Federal Election Commission to ensure there’s a cop on the campaign finance beat.

- Third and finally, we must strengthen ethics laws to ensure that public officials work in the public interest, extend conflict of interest laws to the President and Vice President, require the release of their tax returns, close loopholes that allow former Members of Congress to avoid cooling-off periods for lobbying, break the revolving door between industry and the federal government, and establish a code of conduct for the Supreme Court.

IV. A Closing Thought

By assuring that every American can vote, and has a good reason to vote, we will be undertaking concrete action to advance Dr. King’s dream for America in our time. The reader will find this continuing fidelity to the dream of full citizenship that my ancestor, Scipio Rhame, and his generation passed down to our own, reflected in the thinking that the contributors to this volume of the Harvard Law & Policy Review exemplify—in their teaching, public advocacy, and litigation—and for that, above all, their articles deserve our foremost attention and respect.

To everyone who shares this democratic calling, I will bring this Foreword to a close with this final expression of respect. As I consider the dedication of this journal and its audience to the core of our democracy, I am reminded of a moving experience at Dr. King’s Memorial in Washington, D.C., where a young man approached me and asked to speak.

“Congressman,” the young man at the Memorial informed me, “I only know Dr. King from what I have read in books and seen on TV.”

“You are my Dr. King,” this young man continued. “You are fighting to get me the money to finish college—and helping my parents keep our home. You are helping my cousin get trained for a job—and making certain that my mother has the insurance to pay for her surgery.”

I do not share this conversation out of self-pride. I have done so be-cause everyone in this fight is someone’s Dr. Martin Luther King. From the advocacy of all who read this issue and support progressive ideals, someone will learn that they have rights that others must respect, an absolute good that supports and advances our entire society.

About the Author

Congressman Elijah E. Cummings was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland, where he still resided until his passing. He obtained his bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Howard University, serving as Student Government President and graduating Phi Beta Kappa, and then graduated from the University of Maryland School of Law. Congressman Cummings also received 13 honorary doctoral degrees from Universities throughout the nation.

Congressman Cummings began his career of public service in the Maryland House of Delegates, where he served for 14 years and became the first African American in Maryland history to be named Speaker Pro Tem. From 1996 until his passing in October 2019, Congressman Cummings proudly represented Maryland’s 7th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives. Congressman Cummings served as the Chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Reform and as a senior Member of the U.S. House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

Congressman Cummings was an active member of New Psalmist Baptist Church and is survived by his wife, Dr. Maya Rockeymoore Cummings, and his three children.

Congressman Cummings authored this Foreword prior to his passing, with the assistance of members of his staff: Special Assistant Michael A. Christianson, Counsel Aaron D. Blacks-berg, Legislative Director and Counsel Yvette Badu-Nimako, and Legal Fellow Christina Volcy.

About the American Constitution Society

The American Constitution Society (ACS) believes that law should be a force to improve the lives of all people. ACS works for positive change by shaping debate on vitally important legal and constitutional issues through development and promotion of high-impact ideas to opinion leaders and the media; by building networks of lawyers, law students, judges and policymakers dedicated to those ideas; and by countering the activist conservative legal movement that has sought to erode our enduring constitutional values. By bringing together powerful, relevant ideas and passionate, talented people, ACS makes a difference in the constitutional, legal and public policy debates that shape our democracy.

[1] The King Philosophy, THE KING CTR

[2] Tsahai Tafari, Presidents and their role in civil rights for African Americans, THIRTEEN.

[3] 342 U.S. 350 (1952).

[4] 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

[5] Erin Blakemore, How Dolls Helped Win Brown v. Board of Education, HISTORY, (Mar. 27, 2018)

[6] Id.

[7] Brown Case - Briggs v. Elliott, BROWN FOUND.

[8] J. Y. Smith, A. Philip Randolph Dies at 90, WASH. POST, (May 17, 1979).

[9] See, e.g., Ron Cassie, Up Hill Climb, BALT. (Oct. 2014).

[10] What is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? AMNESTY INT’L UK (Oct. 21, 2017, 12:44 AM).

[11] See Stanford University, Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. RES. EDUC. INST.

[12] See, e.g., Brown vs. Board of Education: 50 Years Later, BALT. SUN (May 16, 2004).

[13] See What is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? supra note 10.

[14] OFFICE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, U.S. DEPT. OF EDUC, 2013-2014 CIVIL RIGHTS DATA COLLECTION 9 (2016), (finding that black students are more than twice as likely to attend schools where more than 20% of teachers are first-year teachers).

[15] BUR. OF LABOR STATISTICS, U.S. DEPT. OF LABOR, LABOR FORCE STATISTICS

FROM THE CURRENT POPULATION SURVEY (2019), (reporting that the unemployment rate in 2018 for white Americans was 3.5% and for African Americans it was 6.5%).

[16] JIAQUAN XU, ET AL., CTR. FOR DISEASE CONTROL, DEATHS: FINAL DATA FOR 2016 10 (2018), (showing that the average life expectancy for black males was 71.5 years old and for white males was 76.1 years old).

[17] EUGENE ROBINSON, DISINTEGRATION: THE SPLINTERING OF BLACK AMERICA 4 (2010).

[18] Id. at 5.

[19] Id. at 74.

[20] Id. at 5.

[21] Id at 105.

[22] See Eileen Patten & Jens Manuel Krogstad, Black Child Poverty Rate Holds Steady, Even as Other Groups See Declines, PEW RESEARCH CTR. (July 14, 2015), (showing that while the overall poverty rate of children is 20%, the poverty rate for black children is 38%).

[23] Neil K. Mehta, Hedwig Lee & Kelly R. Ylitalo, Child Health in the United States: Recent Trends in Racial/Ethnic Disparities, 95 SOC. SCI. & MED. 6, 10 (2013) (finding that black children had the highest percentage of those with fair or poor health than any other race).

[24] Heeju Sohn, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage: Dynamics of Gaining and Losing Coverage over the Life-Course, 36 POPULATION RES. & POL’Y REV. 181, 182–83 (2017) (reporting that a larger percentage of black people are without health insurance than white and Asian Americans).

[25] OFFICE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, U.S. DEPT. OF EDUC, supra note 15, at 9 (showing that black children were more likely to attend schools with high concentrations of inexperienced teachers and that they had less access to high-level science and math classes).

[26] See The King Philosophy, supra note 1.

[27] Martin Luther King, Jr., Give Us the Ballot (May 17, 1957).

[28] Martin Luther King, Jr., I Have a Dream. . . (August 28, 1963).

[29] Danielle Root & Adam Barclay, Voter Suppression During the 2018 Midterm Elections, CTR. FOR AM. PROGRESS (Nov. 20, 2018).

[30] Kim Hart, Exclusive Poll: Only Half of Americans Have Faith in Democracy, AXIOS (Nov. 5, 2018).

[31] See Shelby Cty. v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529, 566–68 (2013) (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

[32] See id. at 556–557 (majority opinion).

[33] See, e.g., id. at 567.

[34] U.S. CONST. amend. XIII, § 2; U.S. CONST. amend. XIV, § 5; U.S. CONST. amend. XV, § 2.

[35] See Shelby, 570 U.S. at 538–39 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting) (describing the 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006 reauthorizations and amendments).

[36] Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006, Pub. L. 109–246, §?2, 120 Stat. 577 (2006).

[37] See Shelby, 570 U.S. at 538–40 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

[38] See John Lewis, Why we still need the Voting Rights Act, WASH. POST (Feb. 24, 2013),

[39] See Shelby, 570 U.S. at 564–66 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

[40] See South Carolina v. Holder, BRENNAN CTR. FOR JUSTICE (Oct. 15, 2012).

[41] See Letter from Thomas Perez, Assistant Attorney General, Dep’t. of Justice, to Keith Ingram, Dir. of Elections, Office of the Tex. Sec’y. of State (Mar. 12, 2012) (on file with ACLU).

[42] See Robert Barnes, Texas redistricting discriminates against minorities, federal court says, WASH. POST (Aug. 28, 2012).

[43] See Shelby, 570 U.S. at 570–78 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

[44] Id. at 559.

[45] Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98, 111 (2000).

[46] See Marcia Henry, After Shelby County v. Holder Voting Rights Are Again a Racial Justice Frontier, 47 J. OF POVERTY L. & POL’Y 258, 256–58 (2013).

[47] See Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2015, H.R. 885, 114th Cong. (2015).

[48] See BRENNAN CTR. FOR JUSTICE, ELECTION 2016: RESTRICTIVE VOTING LAWS BY THE NUMBERS (2016).

[49] See Jelani Cobb, Voter-Suppression Tactics in the Age of Trump, NEW YORKER (Oct. 21, 2018).

[50] See ELECTION 2016: RESTRICTIVE VOTING LAWS, supra note 48.

[51] See BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE, DEBUNKING THE VOTER FRAUD MYTH (2017).

[52] Nico Lang, The real reason black voters didn’t turn out for Hillary Clinton—and how to fix it, SALON (Nov. 10, 2016).

[53] See Katie Brenner, Trump’s Justice Department Redefines Whose Civil Rights to Protect, N.Y. TIMES (Sep. 3, 2018).

[54] See, e.g., History and Enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965: Hearing Before H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 116th Cong. (2019); Subcommittee on Elections, HOUSE COMM. ON HOUSE ADMIN., Press Release, House Comm. on Oversight and Reform, Oversight Democrats Expand Probe to Texas and Kansas (Mar. 28, 2019).

[55] H.R. 1, 116th Cong. (2019).

[56] See Final Vote Results for Roll Call 118, HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES: OFFICE OF THE CLERK, (Mar. 8, 2019, 11:21 AM).

Affirmative Action, Civil rights, Democracy and Elections, Economic Inequality, Equality and Liberty, Race and Criminal Justice, Racial Justice, Voting Rights