A Right-Wing Rout: The Roberts Court's Partisan Opinions

United States Senator from Rhode Island

Download Issue BriefApril 24, 2019

In a new Issue Brief for ACS, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse asserts that “Republican appointees to the Supreme Court have, with remarkable consistency, delivered rulings that advantage the big corporate and special interests that are, in turn, the political lifeblood of the Republican Party.”

Examining the Roberts Court’s output through OT 2017-2018, Senator Whitehouse catalogues 73 partisan majority opinions—joined by only the five conservative members of the Court, against liberal dissenters—in areas spanning voting and money in politics, protection of corporations from liability and regulation, civil rights, and advancing a far-right social agenda. His analysis concludes that in nearly 55 percent of these cases, the “Roberts Five” ignored precedent, congressional findings, and even their favored doctrines, such as originalism and textualism, to reach partisan and corporate-friendly outcomes. This pattern of outcomes speaks to a Roberts Court that, far from calling “balls and strikes,” appears intractably captured by powerful forces of special-interest influence.

You can read the full issue brief below or download this issue brief here.

A Right-Wing Rout: What the “Roberts Five” Decisions Tell Us About the Integrity of Today’s Supreme Court

Sheldon Whitehouse

We’re hearing it more and more: The Supreme Court is as divided as the rest of the city in which it sits. Veteran Court watchers have noticed it. As Norm Ornstein put it, the Supreme Court “is polarized along partisan lines in a way that parallels other political institutions and the rest of society, in a fashion we have never seen.”[1] Others, such as Linda Greenhouse and Jeffrey Toobin, have been more pointed—arguing that the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roberts has become a delivery system for Republican interests.[2] Public opinion polls seem to have picked something up, too. Recent polling by Gallup shows that only 37 percent of respondents have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the Supreme Court[3] and that, while Democrats’ approval of the Court has plummeted (to 40 percent), Republicans’ has more than doubled (to 65 percent).[4] These expert observations, and the shift in attitudes among the public, compel a hard look at the data to find out what the opinions of the Roberts Court show.

It turns out that Republican appointees to the Supreme Court have, with remarkable consistency, delivered rulings that advantage the big corporate and special interests that are, in turn, the political lifeblood of the Republican Party. Several of these decisions have been particularly flagrant and notorious: Citizens United v. FEC, Shelby County v. Holder, and Janus v. AFCME. But there are many. Under Chief Justice Roberts’ tenure through the end of October Term 2017-2018, Republican appointees have delivered partisan rulings not three or four times, not even a dozen or two dozen times, but 73 times. Seventy-three decisions favored Republican interests, with no Democratic appointee joining the majority. On the way to this judicial romp, the “Roberts Five” were stunningly cavalier with any doctrine, precedent, or congressional finding that got in their way.

I. Methodology

The conclusion that the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts has become an instrument of conservative and business interests and Republican donors is admittedly a harsh one. It is important, therefore, to understand how I reach it. The analysis begins with Chief Justice Roberts’s investiture at the beginning of the Supreme Court’s 2005 term and goes through the 2017-2018 term.[5] From 2005 to Justice Scalia’s death in 2016, the conservative wing consisted of Chief Justice Roberts along with Justices Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito. While Justices Stevens and Souter were also appointed by Republican presidents, during this period they had become associated with the Court’s “liberal” wing. When they were replaced by Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, respectively, the 5-4 conservative/liberal spread of the court did not shift. The only change in the Roberts Five line-up during the period this analysis covers occurred when Justice Gorsuch took the seat Justice Scalia previously held.

This review is limited to the Roberts Court’s decisions in civil cases, because those represent the common battleground for vying political and commercial interests—the interests that most directly implicate the financial interests of the Republican establishment. The review further limits the case pool to 5-4 decisions, of which the Roberts Court issued 212 during the period in question.[6]

Of those 212 cases, the most salient for purposes of this analysis are 78 in which the Roberts Five provided all five votes in the majority. Those are the cases where the Court wasn’t just closely divided but was divided along ideological lines—meaning none of the liberal justices (Stevens, Souter, Ginsberg, Breyer, Kagan, or Sotomayor) joined the conservative majority’s analysis. The Roberts Five voting as a bloc does not necessarily indicate partisan purpose, but this is the likeliest pool of cases to find one if it did exist.

I then looked at the 78 cases to see which ones implicated interests associated with the Republican Party. These interests fall into four categories: (1) controlling the political process to benefit conservative candidates and policies; (2) protecting corporations from liability and letting polluters pollute; (3) restricting civil rights and condoning discrimination; and (4) advancing a far-right social agenda. Let’s review these.

First, political control: conservative interests seek to control the political process by giving their corporate, and often secret, big-money benefactors more freedom to spend on elections. This, in turn, helps them drown out opposing voices, manipulate political outcomes and set the agenda in Congress. For proof of this dynamic, look no further than how the Court’s decision in Citizens United proved the death knell for climate change legislation in Congress. Before that fateful decision, which lifted restrictions on corporate spending in candidate elections, Congress had held regular, bipartisan hearings and even votes on legislation to limit the carbon emissions causing climate change. But Citizens United allowed the fossil fuel industry to use its massive money advantage to strike at this bipartisan progress, and it struck hard. The fossil fuel industry set its political forces instantly to work, targeting pro-climate-action candidates, particularly Republicans. Outside spending in 2010's congressional races increased by more than $200 million over the previous midterm's levels—a nearly 450 percent increase.[7] Bipartisanship stopped dead.

Second, protection from courts and regulatory oversight: powerful corporate special interests can become accustomed to disproportionate sway in Congress, where they enjoy outsized influence through political spending and lobbying. With government regulators and in federal courtrooms, this type of influence should make no difference. Some regulators are not captured by the industries they oversee and use the power Congress has given them to protect public health and safety. In courtrooms, corporations may find themselves having to turn over documents that reveal corporate malfeasance. They may find themselves having to tell the truth. And they lose their influence advantage; they may even find themselves being treated equally with real people. In response to this corporate frustration, the Roberts Five have made it harder and harder for regulators and juries to hold corporations accountable.

Third, the Roberts Five are making it harder for people to protect their individual rights and civil liberties. In this group of cases, the conservatives reflect an elitist world view that corporations know best; that courts have no business remedying historical discrimination; that views and experiences outside the typically white, typically male, and typically Christian “mainstream” are not worthy of legal protection. Over and over, the Roberts Five have found ways to make it harder to fight age, gender, and race discrimination.

Finally, there are the “base” issues—abortion, guns, religion—that Republicans use to animate their voters. Republicans promise a Supreme Court that will undo reasonable restrictions on gun ownership and protections for women’s reproductive health, and they use this promise to drive turnout in elections. In this group of cases, the Roberts Five have invalidated federal and state laws, acting as a super-legislature to achieve by judicial fiat what Republicans cannot accomplish through the legislative process.

Seventy-three of the Roberts Five’s 78 partisan, 5-4 cases fall into one of these four categories. In other words, in cases where no other justice joined the conservatives in a 5-4 decision (or in nine cases a 5-3 decision), 92 percent delivered a victory for conservative or corporate donor interests.

The pattern is unmistakable and troubling. What makes it all the more troubling is how often the conservatives abandoned so-called “conservative” judicial philosophies to reach the desired outcome. Members of the conservative wing had assured senators at their confirmation hearings that they would simply “call balls and strikes,”[8] “follow the law of judicial precedent,”[9] and respect the “strong principle” of stare decisis as a limitation on the Court.[10] Once confirmed, they discarded these doctrines when they proved inconvenient to the outcomes the Roberts Five desired. Even the pet conservative doctrine of “originalism” was ignored when necessary. And doctrines about modesty and respect for decisions by elected members of Congress collapsed. In fact, as the Appendix at the end of this Issue Brief catalogues, in nearly 55 percent of the 73 cases, the conservative majority disregarded one or more of the following judicial principles: (1) precedent or stare decisis; (2) judicial restraint; (3) originalism; (4) textualism; or (5) aversion to appellate fact finding.

II. Conservative Outcomes

A. Controlling the Political Process to Benefit Conservatives

Of the Roberts Court’s 73 partisan 5-4 cases, 13 put a thumb on the scale to favor Republicans at the ballot box, by facilitating the flood of dark and corporate money into the political process, by restricting the ability of citizens to vote or have their votes matter, or by working to undermine labor unions, a traditional base of Democratic support.

Four of these 13 cases—FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Davis v. FEC, Citizens United v. FEC, and McCutcheon v. FEC—systemically decimated both the historic Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (also known as McCain-Feingold or BCRA) and prior Court precedents limiting corporate spending in elections.[11] BCRA was first introduced in 1995, and in the Senate, despite dogged opposition by now-Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the bill passed on a 59-41 vote in 2001. Reformers in the House had to resort to a rarely used “discharge petition” to overcome opposition from House leadership and force a vote on the bill, and both chambers finally agreed on legislation that was signed by President George W. Bush in 2002. BCRA was a bipartisan effort by legislators solving problems pragmatically, based on their own experiences as candidates.

The first challenge to BCRA to make it to the Supreme Court, McConnell v. FEC, upheld the main provisions of the law—restrictions on soft money and issue ads—deferring largely to congressional findings.[12] Subsequent BCRA challenges were more successful. What changed? Not the law or the facts, but the composition of the Court: Justice O’Connor, who was the last justice to have any experience running for public office and, therefore, any firsthand knowledge of the effects of money on electoral politics, was replaced by Justice Alito. In short order, out went the ban on issue ads (Wisconsin Right to Life), disclosure requirements for self-funding candidates (Davis), corporate spending (Citizens United) and aggregate contributions limits (McCutcheon). Along the way, the Court, by bare partisan majorities, also knocked out two sensible state-law campaign finance laws in Arizona and Montana.[13]

Out also went respect for precedent, federalism, and judicial restraint. In Citizens United, the most egregious of this slew of cases, Chief Justice Roberts articulated a new standard that if a precedent is “hotly contested”[14]—and justices can “hotly contest” any inconvenient precedent—it has less precedential value and can be replaced. The five-member majority also ignored hundreds of thousands of pages of findings in the Congressional Record, supplanting Congress’s role as the finder of fact, not to mention Congress’s inherent expertise on political issues.

The Roberts Court even trampled on its own procedures to get to its desired result. After all the briefs were filed and oral arguments heard, Chief Justice Roberts scheduled a rehearing and issued new “questions presented,” reframing the narrow challenge to the McCain-Feingold law as a broad question about the ability of the government to regulate corporate spending on elections. This radical procedural maneuver was highly unusual, but it set up the question the conservatives wanted to answer, without a troublesome record to contend with. An elemental restriction on judges is that they must take cases as they come, but as Justice Stevens wrote in dissent, “[f]ive Justices were unhappy with the limited nature of the case before us, so they changed the case to give themselves an opportunity to change the law.”[15] The result was a flood of corporate and corporate front-group money into elections, helping Republican candidates.

The five-justice conservative bloc also set about making it harder for Democrat-leaning minorities to vote. The Fifteenth Amendment prohibits racial discrimination in voting and gives Congress the power to enforce its prohibition by “appropriate legislation.” The Voting Rights Act was originally passed in 1965 to effectuate this prohibition against racial discrimination in voting. Congress reauthorized the Voting Rights Act in 2006, with a factual record of over 15,000 pages, the result of 21 hearings involving scores of witnesses and expert reports. Congress concluded that the facts supported reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act and its pre-clearance provisions for 25 years. The provisions required states and localities with a history of discrimination to have changes to voting procedures pre-cleared by either a court or the Department of Justice before they could take effect. The votes to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act were 390-33 in the House and 98-0 in the Senate.

In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), five justices threw all that out, relying on a newly-created doctrine of “equal sovereignty” among the states and baseless factual findings about race and politics to justify invalidation of the pre-clearance requirements.[16] How did that turn out? State legislatures in the former pre-clearance states went right to work to limit minority voter access. Litigation exploded, and federal judges ended up finding minority voters targeted with “surgical precision.”[17] This was done with no regard for the “conservative” doctrine of judicial restraint, or the principle that an appellate court ought to leave findings of fact to others.

The Roberts Five also permitted aggressive racial and partisan gerrymandering,[18] limited the rights of minorities to challenge racially concentrated districts,[19] allowed purges of voting rolls that have been shown to disproportionately disqualify minority votes,[20] and permitted voting under electoral maps that a federal district court concluded were drawn with racially discriminatory intent.[21] Every single map and policy upheld had been crafted by Republican legislatures and politicians.

Finally, starting with Harris v. Quinn in 2014 and concluding with Janus v. AFSCME in 2018, the 5-4 conservative bloc targeted a long-time Republican bugaboo: public-sector union political spending. At stake was the unanimous 1977 precedent Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, which upheld public sector unions’ practice of collecting from non-union members funds, called ”agency shop fees,” to cover the cost of collective bargaining that benefits members and nonmembers alike.[22] Abood annoyed the union-busting right wing, which plotted its demise for years. The Supreme Court had reaffirmed Abood numerous times; more than 20 states had enacted statutes consistent with the case since it was decided; and public entities of all stripes had entered into multiyear contracts with unions following Abood’s guidance. Respect for precedent, unanimous reaffirmance, and reliance interests all militated in favor of the Court upholding this 40 year-old precedent. Under Chief Justice Roberts, however, settled law can become “hotly contested,” and led by Justice Alito, the conservatives hotly contested this area of the law.

First, in a case involving public employee unions, Justice Alito digressed from the question presented to raise questions about the constitutionality of the unions’ agency shop fees, all but directly inviting a challenge to Abood.[23] Next, in Harris, the five conservatives further unsettled this settled area of the law by concluding the First Amendment prohibited the collection of an agency shop fees from home health care providers who do not wish to join or support a union. Justice Alito ignored the traditional conservative doctrines of federalism and states’ rights by concluding home health care workers were not “full-fledged” government workers although Michigan had designated them as such.[24] Finally, in a surprise to no one, the Court overruled Abood in Janus in 2018.[25] In dissent, Justice Kagan aptly summed up the conservatives’ naked judicial activism:

Rarely if ever has the Court overruled a decision—let alone one of this import—with so little regard for the usual principles of stare decisis. There are no special justifications for reversing Abood. It has proved workable. No recent developments have eroded its underpinnings. And it is deeply entrenched, in both the law and the real world . . . . Reliance interests do not come any stronger than those surrounding Abood. And likewise, judicial disruption does not get any greater than what the Court does today.[26]

B. Protecting Corporations from Liability and Letting Polluters Pollute

In 33 cases—the largest category by far, full of hugely important decisions that rarely make front-page news—the Roberts Five have engaged in a two-front effort to insulate corporations from liability: they have limited the ability of government agencies to regulate corporate acts; and they have made it harder for individuals harmed by corporate acts to have their rights vindicated in court. This one-two punch has made it increasingly hard for Congress and the states to protect public health and welfare, and has eroded the Seventh Amendment’s guarantee of the right to a civil jury, a right which James Madison said was as “essential to secure the liberty of the people as any one of the pre-existent rights of nature.”[27]

Environmental protection has borne the brunt of the Roberts Five’s anti-regulatory zeal, freeing big corporations to pollute. This majority has rejected federal claims under the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy, and the Clean Air Act.[28] It has denied environmental groups standing and used the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment to make it harder for state and local governments to regulate development.[29] It also took an unprecedented procedural path to block the Clean Power Plan.[30]

Corporations have fewer limitations on their commercial transactions thanks to the Roberts Five. Corporations have seen this conservative majority weaken the federal antitrust law to the detriment of consumers,[31] and make it harder for consumers and investors to obtain accurate information.[32] The Roberts Five have even given more leeway to treat corporate executives better and employees worse.[33]

The Roberts Five’s pro-corporate policy preference has been particularly evident in aggressive judicial expansion of the Federal Arbitration Act of 1925 (FAA). Their decisions have made this an avenue for powerful and wealthy interests to systematically deny ordinary individuals, like employees and customers, access to juries of their peers when wronged.

In 14 Penn Plaza v. Pyett, the Court held 5-4 that unions could bargain away workers’ rights to have age discrimination claims heard in court.[34] In Rent-A-Center v. Jackson, the same right-wing bloc held that would-be litigants challenging an arbitration agreement as unconscionable would have to challenge the unfairness of the arbitration before the very arbitrator whose legitimacy to hear the case they disputed.[35] Also in 2010, the Court prohibited the use of class arbitration unless all parties specifically agreed to it.[36] Less than a year later, in AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, the Robert Five prevented consumers from bringing class-action suits against corporations for low-dollar, high-volume frauds.[37] In American Exp. Co. v. Italian Colors Restaurant, the Court struck again, this time 5-3, dispensing with the rule—established by a long line of Supreme Court precedent—that contractual arbitration clauses are enforceable only so far as they actually permit individuals to vindicate their rights.[38] And last term, Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, another 5-4 partisan decision, further diminished employees’ right to join their individual claims in the courtroom, allowing the FAA to swallow the National Labor Relations Act so that employment contracts can force employees to waive statutory labor rights.[39]

You’ll be hard-pressed to find any mention of the jury trial protections of the Seventh Amendment in these cases. So much for the doctrine of originalism.

For those lucky enough not to be ensnared in an arbitration agreement, actually getting to a jury of one’s peers is more difficult than ever. In 1938, the federal courts, through the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, adopted a notice pleading standard with Rule 8(a)(2) requiring simply a “short and plain statement of the claim.” The idea was that, since plaintiffs often lack detailed information about their claim when they first file suit, they should be able to survive a motion to dismiss and reach the discovery stage without pleading the facts with particularity.

Discovery can be costly, embarrassing, and often damaging to corporate defendants, giving them a strong incentive to prevent it. The 5-4 conservative majority took a big step toward insulating corporations from discovery obligations in Ashcroft v. Iqbal (2009), where it heightened the “plausibility” standard the Court first announced in a 7-2 decision in AT&T v. Twombly, and signaled to lower court judges that they had a freer hand to dismiss cases before discovery.[40] The leading student of federal court civil procedure, Professor Arthur Miller, observed, “insisting on more pleading detail—on pain of dismissal—is not consistent with the view of American courts as democratic institutions committed to the resolution of civil disputes on their merits in an egalitarian, transparent fashion.”[41] According to Miller, Justice Souter, who authored Twombly but dissented in Iqbal, thought Iqbal’s extension of Twombly beyond its facts was “entirely arbitrary and failed to guide the lower courts on how to draw the fact-conclusion distinction.”[42] The door had been opened a crack; the Roberts Five took advantage and thrust it open all the way.

Class action litigation has long provided redress for low-dollar, many-victim frauds. The 5-4 conservative majority threw out a class action by 1.6 million women alleging gender discrimination by Wal-Mart, making it harder for members of a purported class to prove they have sufficiently common claims.[43] The Court also made it harder for groups of individuals to bring common claims[44] and has made it harder for plaintiffs’ attorneys to receive enhanced attorneys fee awards.[45] And finally, the Court has simply barred altogether certain claims for relief under the Privacy Act, Family Medical Leave Act, False Claims Act, and Alien Tort Statute.[46]

C. Restricting Civil Rights and Condoning Discrimination

The Roberts Five have shown a persistent animosity toward civil rights and liberties, consistent with right-wing Republican priorities. A representative illustration of the eighteen cases in this category is Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire (2007), in which the conservative majority threw out a woman’s gender pay discrimination claim because she hadn’t been aware of the pay disparity sooner.[47] Congress overturned that decision with the passage of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, the first bill signed into law by President Obama.

The five conservatives have delivered similar decisions limiting the ability of public schools to use affirmative action to achieve diversity and provide access to English as a Second Language Programs;[48] of Native Americans to challenge the discriminatory practices of banks;[49] and of employees to bring age discrimination claims and employment discrimination claims.[50] Protections for discrimination against immigrants have also been eroded by the Court’s conservative majority.[51]

In civil liberties cases, too, the Roberts Five repeatedly take the side of the government. They have limited First Amendment speech protections for public employees and students,[52] despite expanding the First Amendment for corporations at seemingly every opportunity.[53] The have made it harder to challenge potentially unlawful government surveillance,[54] and have limited the ability of prisoners to seek redress for harm under 42 U.S.C. § 1983,[55] the Fourth Amendment,[56] and the Eighth Amendment.[57]

D. Advancing a Far-Right Social Agenda

The final nine cases on the list advance a far-right social agenda—three of them restricting the rights of women to make choices about their reproductive health. This has been a top motivating force for conservative voters, and legal victories in high-profile cases help Republican politicians motivate their “base” without having to face the work and peril of legislating. In Carhart, Hobby Lobby, and NIFLA, the Roberts Five delivered anti-choice victories to the religious right.[58] This same constituency saw four partisan victories in cases involving the separation of church and state: Hein, Buono, Winn, and Galloway.[59]

A decades-long political effort by the National Rifle Association to expand gun rights through the Second Amendment paid off in the 5-4 Heller and McDonald decisions. Heller was a radical shift in Second Amendment jurisprudence, in which the Court inferred for the first time in our history an individual right to keep and bear firearms for self-defense. No less an observer than Judge Posner has noted that “[t]he true springs of the Heller decision must be sought elsewhere than in the majority’s declared commitment to originalism.”[60] That “elsewhere” is not too hard to find. Since 1990, 84 percent of the NRA’s political contributions, nearly $19 million, has gone to Republican politicians.[61]

Heller and McDonald present naked “judicial activism.” As Justice Stevens noted is his Heller dissent,

this thicket will have on that ongoing debate—or indeed on the Court itself—is a matter that future historians will no doubt discuss at length. It is, however, clear to me that adherence to a policy of judicial restraint would be far wiser than the bold decision announced today.[62]

As a tide of tragic gun massacres continues to sweep this country, and with the Court set to decide another high-stakes gun case next term, Americans should keep their eyes on the Roberts Five and their pattern of victories for important interests of the Republican Party.

III. A History and Future of Court Capture

There is a pattern in the Roberts Era: 73 partisan decisions, in which the majority was composed of only the five Republican-appointed justices, that handed a win to big conservative and corporate interests. Quite often, these same decisions override or ignore conservative judicial principles. It is hard to review this pattern and conclude that the outcomes are attributable to coincidence and not design. When big conservative and corporate interests are at stake, the Roberts Five readily overturn precedent, invalidate statutes passed by wide bipartisan margins, and opine on broad constitutional issues they need not reach. Modesty, originalism, stare decisis, and even federalism—all supposedly conservative judicial principles—have been jettisoned when necessary to deliver these seventy-three partisan Republican wins.

The Roberts Court’s pro-corporate bent has been well documented. The Constitutional Accountability Center (CAC) has tracked one measure of this—how the United States Chamber of Commerce has fared when it has taken a position before the Court. The Chamber represents big corporate interests and supports Republican candidates. Since 2006, when the Roberts Five conservative bloc first solidified, the Chamber has won 70 percent of the time, compared with a win rate of 56 percent from 1994 to 2005. To be sure, many of the Chamber’s wins have come with one or more liberal votes. But according to the CAC, “five conservative Justices now on the bench have given the Chamber more than three quarters of their total votes (77.2%), while the four moderate-to-liberal Justices have given roughly half (50.5%).”[63] Justice Gorsuch has become the Chamber’s most reliable vote, siding with it 93 percent of the time. Justice Kavanaugh’s pro-Chamber record on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit suggests this trend will continue now that he has joined the Five.

This undeniable pattern helps explain the mad scramble by right-wing interest groups and their Republican allies in the Senate to protect the Roberts Five at all costs, whether by refusing to even consider Chief Judge Merrick Garland, a moderate jurist nominated by a Democratic president, or by breaking longstanding Senate norms and traditions to ram through Judge Kavanaugh, a flawed Trump nominee, eighteen months later.

Republicans under Donald Trump now do not even try to hide the fact that they have “insourced” the judicial vetting process to these same interest groups, coordinated by the Federalist Society and its political gatekeeper Leonard Leo.[64] The big funders of the Federalist Society in turn benefit financially from the Court’s pro-corporate tilt. To the extent its funders are public (many are secret), they come as no surprise: the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Koch brothers, the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, and the Scaife Foundations—a who’s-who of big Republican influencers.[65]

Once nominees are selected, the Judicial Crisis Network, funded as far as can be determined by big business and partisan groups, runs dark-money political campaigns to influence senators to support confirmation.[66] It worked for both Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. Who exactly pays millions of dollars for that, and what their expectations and understandings are, is another secret.

Once the nominee is on the Court, business front groups with ties to funders of the Republican political machine file amicus briefs to signal their wishes to the Roberts Five. Who is really behind those “friends of the Court” is kept secret, but some patterns have emerged there, too. We know there are repeat players—that, for instance, the Pacific Legal Foundation and the Center for Constitutional Rights filed briefs in Citizens United, Shelby, and Hobby Lobby, and the Cato Institute filed briefs in those same three cases plus NIFLA.

Janus, and its forebear Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, show how conservative amici work in lockstep and fundraise off their efforts. Friedrichs was underwritten by the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, which has openly acknowledged its goal of “reduc[ing] the size and power of public sector unions.”[67] The Bradley Foundation not only bankrolled the nonprofit law firm bringing that case, but also donated to 11 different organizations that filed amicus curiae briefs supporting the plaintiffs. Many resurfaced in Janus. In out-of-court statements, these amici trumpeted their confidence in a pre-ordained outcome.[68] And the Bradley Foundation is a longtime supporter of the Federalist Society, where the selection of nominees to the Court began.[69]

We have reached the point where it appears the same set of big-money players is selecting nominees to our highest court, then spending millions of dollars to campaign for their confirmation, and then funding amicus briefs designed to signal a preferred outcome to those nominees once they have ascended to the bench. The pattern apparent in the spending and amicus presence of big Republican donor interests intersects in ominous ways with the pattern of those 73 partisan decisions by the Roberts Five giving wins to key conservative and corporate interests. It’s no wonder that Americans increasingly feel the game is rigged.

Americans deserve to understand how that rigged game works. Further light must be shed. While we do not yet have a complete view of the ways these interests have captured the conservative bloc of the Court—many are still hidden in the shadow of dark money—the overall picture is coming into the light. It is a picture in which money, influence, and partisanship, rather than objective legal analysis and interpretation, are reshaping some of the most important areas of the law in the United States. Although the pattern of special-interest funding is still indistinct, the pattern of 73 partisan 5-4 decisions under Chief Justice Roberts is undeniable.

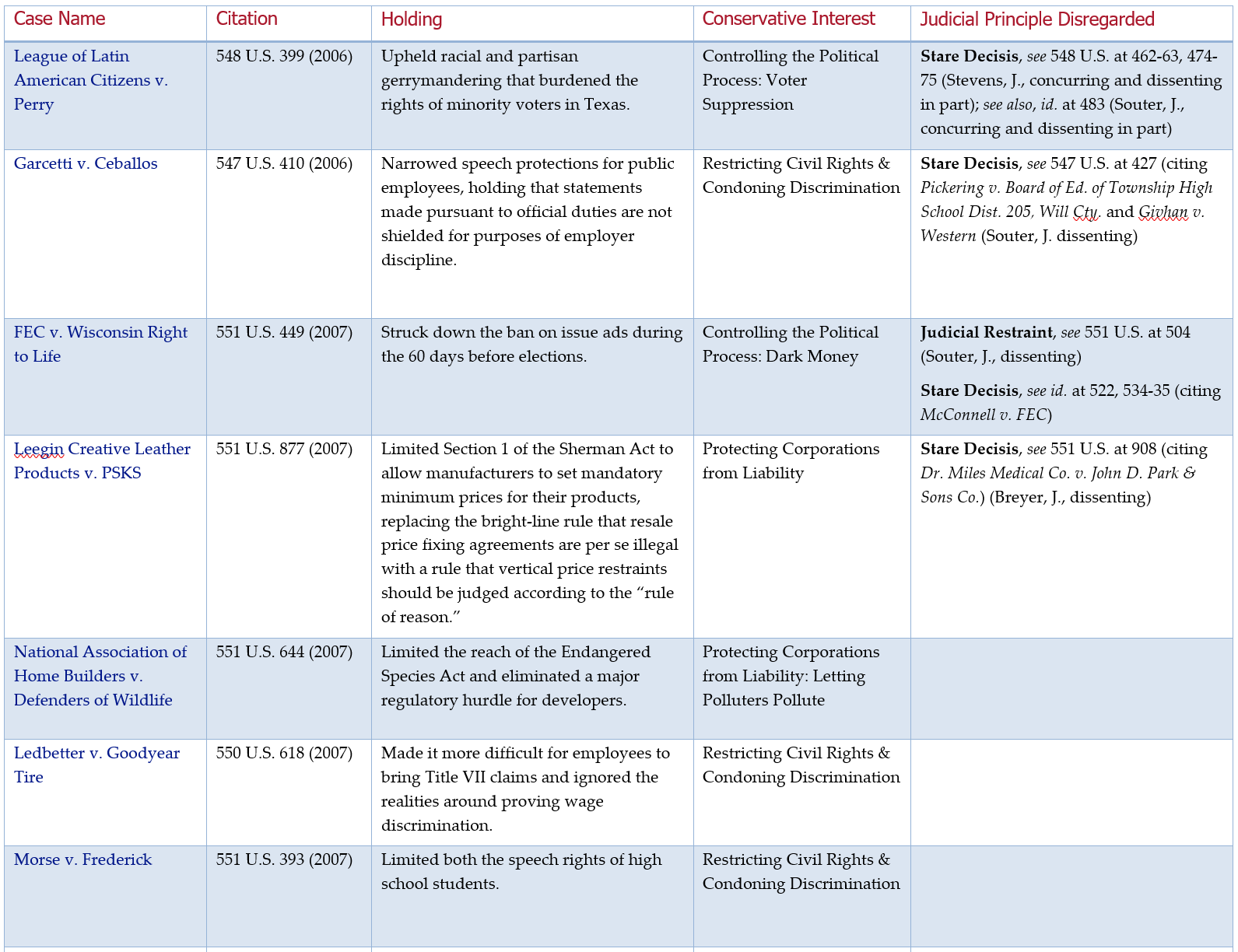

Appendix

Roberts Five Decisions

The following 73 cases are those in which a majority opinion by the Roberts Five (Justices Roberts, Alito, Kennedy, Thomas, and Scalia or Gorsuch) served one of the following conservative interests: (1) controlling the political process to benefit conservative candidates and policies; (2) protecting corporations from liability and letting polluters pollute; (3) restricting civil rights and condoning discrimination; and (4) advancing a far-right social agenda.

Where appropriate the appendix also identifies the judicial principles these conservative justice generally espouse, but which they arguably disregarded in these cases to achieve a desired outcome, including: (1) stare decisis; (2) judicial restraint; (3) originalism; (4) textualism; and (5) aversion to fact finding.

About the Author

In the United States Senate, Sheldon Whitehouse has fought to strengthen campaign finance laws, increase transparency in government, and defend the rule of law. He leads the effort to pass the DISCLOSE Act, to end the flood of undisclosed dark money polluting our elections. He has conducted rigorous oversight of the executive branch to root out ethical abuses. He is also an outspoken advocate for protecting access to justice so each American can have their day in court.x

A graduate of Yale University and the University of Virginia School of Law, Sheldon served in multiple senior roles in Rhode Island government before his appointment by President Clinton as Rhode Island’s United States Attorney in 1994. Sheldon was elected Attorney General of Rhode Island in 1998, and in 2006 to the Senate, where he serves on the Judiciary Committee; the Budget Committee; the Environment and Public Works Committee; and the Finance Committee.

About the American Constitution Society

The American Constitution Society (ACS) believes that law should be a force to improve the lives of all people. ACS works for positive change by shaping debate on vitally important legal and constitutional issues through development and promotion of high-impact ideas to opinion leaders and the media; by building networks of lawyers, law students, judges and policymakers dedicated to those ideas; and by countering the activist conservative legal movement that has sought to erode our enduring constitutional values. By bringing together powerful, relevant ideas and passionate, talented people, ACS makes a difference in the constitutional, legal and public policy debates that shape our democracy.

[1] Norm Ornstein, Why the Supreme Court Needs Term Limits, Atlantic (May 22, 2014).

[2] See, e.g., Jeffrey Toobin, No More Mr. Nice Guy, New Yorker (May 25, 2009); Linda Greenhouse, Polar Vision, N.Y. Times (May 28, 2014); Linda Greenhouse, Supreme Court Party Time, N.Y. Times (Nov. 22, 2018).

[3] Megan Brenan, Confidence in Supreme Court Modest, but Steady, Gallup (July 2, 2018).

[4] Justin McCarthy, GOP Approval of Supreme Court Surges, Democrats’ Slides, Gallup (Sept. 28, 2017).

[5] The replacement of Justice Kennedy with Justice Kavanaugh, his former law clerk, keeps the Roberts Five conservative bloc intact.

[6] Included in the 5-4 decisions discussed in this article are the eight 5-3 decisions where a justice recused him or herself (for example, Justice Kagan recused herself from cases on which she worked as solicitor general) and one decision from when the Court had only eight members, specifically the period after Justice Scalia died.

[7] Total Outside Spending by Election Cycle, Excluding Party Committees, Ctr. for Responsive Pol. (last visited Apr. 10, 2019).

[8] Roberts: ‘My Job Is to Call Balls and Strikes and Not to Pitch or Bat,’ CNN (Sept. 12, 2005).

[9] Confirmation Hearing on the Nomination of Hon. Neil M. Gorsuch To Be An Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States: Hearing Before S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 115th Cong. (2017) (statement of then-Judge Neil Gorsuch).

[10] Senate Confirmation Hearings: Day 2, N.Y. Times (Jan. 10, 2006) (nomination hearing of Samuel Alito); see also Confirmation Hearing on the Nomination of Hon. Clarence Thomas To Be An Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States: Hearing Before S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 102d Cong. (1991) (“[Y]ou cannot simply, because you have the votes, begin to change rules, to change precedent.”).

[11] FEC v. Wis. Right to Life, 551 U.S. 449 (2007) (holding that “BCRA's prohibition on use of corporate funds to finance ‘electioneering communications’ during pre-federal-election periods violated corporation's free speech rights when applied to its issue-advocacy advertisements”); Davis v. FEC, 554 U.S. 724 (2008) (holding that BCRA’s spending threshold and disclosure requirements violate the First Amendment); Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) (holding that “federal statute barring independent corporate expenditures for electioneering communications violated First Amendment”); McCutcheon v. FEC, 572 U.S. 185 (2014) (holding “that the statutory aggregate limits on how much money a donor may contribute in total to all political candidates or committees violated the First Amendment”).

[12] See McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93, 132 (2003) (“In BCRA, Congress enacted many of the [Senate Government Affairs] committee’s proposed reforms. BCRA’s central provisions are designed to address Congress concerns about the increasing use of soft money and issue advertising to influence federal elections.”).

[13] Ariz. Free Enter. Club v. Bennett, 564 U.S. 721 (2011) (holding that the state’s interest in equalizing electoral funding could not justify the substantial burden on political speech imposed by a state statute’s matching funds provision); Am. Tradition P’ship v. Bullock, 567 U.S. 516, 516 (2012) (holding that a state law providing that a “corporation may not make an expenditure in connection with a candidate or a political committee that supports or opposes a candidate or a political party” violates First Amendment political speech rights).

[14] Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310, 379 (2010).

[15] Id. at 398 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

[16] Shelby Cty. v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529, 542, 550-52 (2013).

[17] N.C. State Conference of NAACP v. McCrory, 831 F.3d 204, 214 (4th Cir. 2016).

[18] League of Latin Am. Citizens v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006).

[19] Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1 (2009).

[20] Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Inst., 138 S. Ct. 1833 (2018).

[21] Abbott v. Perez, 138 S. Ct. 2305 (2018).

[22] Abood v. Detroit Bd. of Educ., 431 U.S. 209 (1977).

[23] Knox v. Serv. Emps. Int’l Union, Local 1000, 567 U.S. 298 (2012). Justices Ginsberg and Sotomayor concurred in the judgment of Justice Alito’s 7-2 majority opinion in Knox v. Service Employees International Union. In her concurring opinion, Justice Sotomayor (joined by Justice Ginsberg) wrote that she could not “agree with the majority’s decision to address unnecessarily significant constitutional issues well outside the scope of the questions presented and briefing. By doing so, the majority breaks our own rules and, more importantly, disregards principles of judicial restraint that define the Court’s proper role in our system of separated powers.” Id. at 323 (Sotomayor, J., concurring).

[24] Harris v. Quinn, 573 U.S. 616, 645-46 (2014).

[25] If there was any surprise here, it was that Abood wasn’t overturned earlier. The issue had been teed up for the five conservatives in 2016 in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, 136 S. Ct. 1083 (2016) (mem.), but Justices Scalia’s death left the Court deadlocked 4-4. I describe in greater detail the procedural machinations behind these cases and the extensive right-wing dark money support they received in an amicus brief in Janus. Brief of Senators Sheldon Whitehouse and Richard Blumenthal as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, Janus v. Am. Fed’n of State, Cty., & Mun. Emps., Council 31, 138 S. Ct. 2448 (2018).

[26] Janus, 138 S. Ct. at 2487-88 (Kagan, J., dissenting).

[27] The Papers of James Madison (William T. Hutchinson et al. eds., 1962).

[28] Nat’l Ass’n of Home Builders v. Defenders of Wildlife, 551 U.S. 644 (2007) (holding that a scheme to transfer federal permitting power under the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System to officials of state was not subject to the Endangered Species Act requirement that federal agencies ensure that their actions do not jeopardize endangered species); Winter v. NRDC, 555 U.S. 7 (2008) (holding that alleged irreparable injury to marine mammals resulting from Navy's training exercises using mid-frequency active sonar was outweighed by the public interest and the Navy's interest in effective, realistic training of its sailors); Michigan v. EPA, 135 S. Ct. 2699 (2015) (ignoring EPA’s cost-benefit analysis to hold that its regulation of hazardous air pollutants emitted by power plants was unreasonable for failing to consider the cost of compliance).

[29] Summers v. Earth Island Inst., 555 U.S. 488 (2009) (restricting the right of environmental groups by holding that they do not suffer any ‘concrete injury’—and therefore do not have standing to sue—when the Forest Service allows logging in a national forest without following legally required procedures); Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Mgmt. Dist., 570 U.S. 595 (2013) (holding that the government conditioning issuance of a permit on a landowner paying money to improve public wetlands is a constitutional taking).

[30] See, Lawrence Hurley & Valerie Volcovici, U.S. Supreme Court Blocks Obama’s Clean Power Plan, Sci. Am. (Feb. 9, 2016).

[31] Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, 551 U.S. 877 (2007) (holding that federal antitrust laws allows manufacturers to set mandatory minimum prices for their products based on a “rule of reason” standard, replacing the previous bright-line rule that such price fixing agreements are per se illegal); Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274 (2018) (holding that federal antitrust laws do not prohibit credit card companies from barring merchants from steering customers toward alternative payment methods).

[32] Stoneridge Inv. Partners v. Scientific-Atlantic, 552 U.S. 148 (2008) (holding that in order to sue for securities fraud, shareholders must show that they relied on the alleged fraudulent behavior in making their decision to acquire or hold stock); Pliva v. Mensing, 564 U.S. 604 (2011) (holding that federal law preempts state tort law against generic drug makers who failed to warn consumers about dangerous side effects); Janus Capital Grp., Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, 564 U.S. 135 (2011) (holding that liability for securities fraud is limited to individuals or entities with “ultimate authority” over the misstatements, regardless of who contributed to those statements); Mut. Pharm. v. Bartlett, 133 S. Ct. 2466 (2013) (holding that federal law preempts state design defect claims, thereby restricting plaintiffs’ ability to sue generic drug manufactures under state law for failure to adequately label medication).

[33] Wis. Cent. Ltd. v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 2067 (2018) (holding that railroad executives are exempt from federal employment taxes on stock-based compensation); Conkright v. Frommert, 559 U.S. 506 (2010) (holding that courts are required to defer to a trust administrator’s exercise of discretion even when the trustee's previous construction of the same terms was found to violate ERISA); Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp., 567 U.S. 142 (2012) (expanding fair wage exemptions under the Fair Labor Standards Act, depriving certain categories of workers of statutory fair pay protections); Encino Motorcars v. Navarro, 136 S. Ct. 2117 (2016) (further expanding exemptions from the Fair Labor Standards Act to deprive certain categories of workers statutory fair pay protections).

[34] 14 Penn Plaza v. Pyett, 556 U.S. 247 (2009).

[35] Rent-a-Center, West, Inc. v. Jackson, 561 U.S. 63 (2010).

[36] Stolt-Nielsen S.A. v. AnimalFeeds Int’l, 599 U.S. 662 (2010).

[37] AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011).

[38] Am. Express Co. v. Italian Colors Rest., 570 U.S. 228 (2013).

[39] Epic Sys. Corp. v. Lewis, 138 S. Ct. 1612 (2018).

[40] Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662 (2009).

[41] Arthur R. Miller, From Conley to Twombly to Iqbal: A Double Play on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 60 Duke L.J. 1, 71 (2010).

[42] See id. at 25.

[43] Wal-Mart Stores v. Dukes, 564 U.S. 338 (2011).

[44] See Genesis Healthcare Corp. v. Symczk, 569 U.S. 66 (2013) (limiting plaintiffs’ ability to bring collective action claims under the Fair Labor Standards Act); Comcast v. Behrend, 569 U.S. 27 (2013) (making class action certification more difficult and limited suits against corporations for low-dollar, high-volume antitrust violations); Cal. Pub. Emps.’ Ret. Sys. v. Anz Sec., Inc., 137 S. Ct. 2042 (2017) (making it harder for individual investors to protect their rights via class action).

[45] Perdue v. Kenny A, 559 U.S. 542 (2010) (heightening standards for civil rights plaintiffs’ attorneys to receive compensation for their services).

[46] See FAA v. Cooper, 566 U.S. 284 (2012) (making it more difficult for plaintiffs to recover for intangible harms caused by government privacy violations); Coleman v. Court of Appeals of Md., 566 U.S. 30 (2012) (limiting plaintiffs from bringing suits against states for denying them sick leave under the Family Medical Leave Act); Schindler Elevator Corp. v. U.S. ex rel. Kirk, 563 U.S. 401 (2011) (limiting the ability of plaintiffs to bring suit as whistleblowers on behalf of the government); Jesner v. Arab Bank, 138 S. Ct. 1386 (2018) (holding that foreign corporations may not be sued under the Alien Tort Statute, protecting them from liability for human rights abuses).

[47] Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire, 550 U.S. 618 (2007).

[48] See Parents Involved in Community Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007) (holding that compelling interest of promoting diversity in higher education could not justify primary and secondary public schools to use affirmative action programs); Horne v. Flores, 557 U.S. 433 (2009) (holding that inadequate funding for English as a Second Language programs did not violate federal law absent showing that state was not fulfilling its obligation by “other means”).

[49] See Plains Commerce Bank v. Long Family Land and Cattle Co., 554 U.S. 316 (2008) (holding that a Tribal Court does not have jurisdiction to adjudicate a claim against a bank based on in its on-reservation commercial dealings treating applicants disadvantageously because of their tribal affiliation and racial identity).

[50] See Gross v. FBL Fin. Servs., 557 U.S. 167 (2009) (heightening the standard for age discrimination claims and making it more difficult for victims to obtain relief); Ricci v. Destefano, 557 U.S. 557 (2009) (holding that absent strong basis in evidence to believe there existed an equally valid, less-discriminatory alternative to use of examinations that served city's needs, a city must use current exam even though it has a disparate impact on minority applicants seeking promotions); Vance v. Ball State Univ., 570 U.S. 421 (2013) (making it harder for plaintiffs to bring workplace harassment claims, by limiting claims based on harassment by coworkers who are not supervisors); Univ. of Tex. Southwestern Med. Ctr. v. Nassar, 570 U.S. 338 (2013) (increasing the standard of proof for employer retaliation claims, making these claims more difficult to bring).

[51] See Chamber of Commerce of U.S. v. Whiting, 563 U.S. 582 (2011) (holding federal immigration law does not preempt state law that allows for suspension and revocation of business licenses for hiring undocumented immigrants); Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392 (2018) (allowing the discriminatory Muslim ban to go into effect and restricted immigration from eight, mostly Muslim-majority, countries, despite explicit statements by President Trump about the ban’s discriminatory intent); Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S. Ct. 830 (2018) (allowing immigrants to be detained for prolonged periods of time without a bail hearing).

[52] See Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006) (narrowed speech protections for public employees, holding that statements made pursuant to official duties are not shielded for purposes of employer discipline); Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007) (limiting the speech rights of high school students).

[53] See, e.g., Tamara R. Piety, Corp. Reform Coal., The Corporate First Amendment (2015).

[54] Clapper v. Amnesty Int’l USA, 568 U.S. 398 (2013) (denying plaintiffs standing even if they claim a reasonable likelihood that their communications will be illegally intercepted by the government under FISA surveillance).

[55] See Dist. Attorney’s Office for the Third Judicial Dist. v. Osborne, 557 U.S. 52 (2009) (holding that the Due Process Clause does not require states to turn over DNA evidence to a plaintiff post-conviction); Connick v. Thompson, 563 U.S. 51 (2011) (making it harder to hold prosecutors’ offices liable for the illegal misconduct of individual prosecutors); Murphy v. Smith, 138 S. Ct. 784 (2018) (reducing compensation for prisoners when government officials violate their constitutional rights).

[56] See Florence v. Bd. of Chosen Freeholders of Cty. of Burlington, 566 U.S. 318 (2012) (allowing strip searches of inmates without reasonable suspicion, reducing the Fourth Amendment protections of arrestees).

[57] See Glossip v. Gross, 135 S. Ct. 2726 (2015) (making challenging execution methods more difficult and thus limiting prisoners’ Eighth Amendment rights).

[58] See Gonzalez v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007) (making it harder for women to exercise their reproductive rights by holding Congress's ban on partial-birth abortion was not unconstitutionally vague and did not impose an undue burden on the right to an abortion); Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, 134 S. Ct. 2751 (2014) (permitting corporations to deny contraception based on objections to facially neutral, non-discriminatory laws); NIFLA v. Becerra, 138 S. Ct. 2361 (2018) (striking down a California law mandating disclosure related to available medical services for pregnant women, potentially deceiving women into believing that anti-abortion pregnancy centers are medical clinics).

[59] See Hein v. Freedom From Religion Found., 551 U.S. 587 (2007) (restricting the ability of citizens to sue the government under the First Amendment for entangling church and state); Salazar v. Buono, 559 U.S. 700 (2010) (allowing a cross to remain on federal property, eroding the separation of church and state); Ariz. Christian Sch. Tuition Org. v. Winn, 563 U.S. 125 (2011) (making it harder for plaintiffs to challenge Establishment Clause violations in court); Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. 565 (2014) (allowing legislative prayer even when a town fails to represent a variety of religions in its meetings). Of course, church-state issues do not always break down along partisan lines, as Justices Breyer’s and Kagan’s vote with the majority in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012 (2017), demonstrated. Nevertheless, the Roberts Five has reliably proven to be a voting bloc on these issues.

[60] Richard A. Posner, In Defense of Looseness, New Republic (Aug. 27, 2008).

[61] National Rifle Assn, OpenSecrets.org (last visited Dec. 4, 2018).

[62] District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 680 n. 39 (2008) (Stevens, J., dissenting).

[63] Brian F. Frazelle, A Banner Year for Business as the Supreme Court’s Conservative Majority Is Restored, Const. Accountability Ctr. (July 17, 2018).

[64] Todd Ruger, Senate Republicans Steamroll Judicial Process, Roll Call (Jan. 18, 2018).

[65] The Money Behind Conservative Legal Movement, N.Y. Times, (Mar. 19, 2017).

[66] Anna Massoglia & Kaitlin Washburn, Only a Fraction of ‘Dark Money’ Spending on Kavanaugh Disclosed, OpenSecret.org (Oct. 24, 2018).

[67] Priority Giving Areas, Lynde & Harry Bradley Found. (last visited Feb. 11, 2019). See Brian Mahoney, Conservative Group Nears Big Payoff in Supreme Court Case, Politico (Jan. 10, 2016); Adele M. Stan, Who’s Behind Friedrichs?, Am. Prospect (Oct. 29, 2015).

[68] See, e.g., Brief of Senators Sheldon Whitehouse & Richard Blumenthal as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents at Appendix at A-1, A-7, Janus v. Am. Fed’n of State, Cty, & Mun. Emps., Council 31, 138 S. Ct. 2448 (2018) (No. 16-1466), (“A Judgment Day is coming very soon. . . . As a result [of the Court’s grant of certiorari in Janus], we may well be on the verge of an historic victory over government unions . . . unions . . . We are very confident that the Supreme Court is about to rule [shop fees] illegal on a national scale—but that will just be the beginning.”); Press Release, Freedom Foundation, Freedom Foundation Files Amicus Briefs in Landmark Right-to-Work Case (Dec. 6, 2017) (“The second Freedom Foundation amicus brief assumes the Janus ruling will invalidate Abood and urges the justices to include wording in it that would make enforcement easier.”); Will Government Union Gravy Train Come to an End?, Competitive Enterprise Inst. (Sept. 20, 2017) (“A nearly identical lawsuit over the constitutionality of forced union dues was heard by the Court in 2016, but the untimely death of Justice Antonin Scalia led to a 4-4 split. The justices may want to take another shot at the issue with a full court.”); How Government Unions Plan to Keep Members and Dues Flowing After Janus, Competitive Enterprise Inst. (Oct. 27, 2017) (“Government unions are preparing for a world where they can no longer force non-members to pay dues in the public sector.”); Tom Gantert, Supreme Court Could Bring Right-To-Work To Government Employees Nationwide, Mich. Cap. Confidential (Sept. 30, 2017) (“If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Janus, as is expected, it would have the same effect as establishing a right-to-work law for public sector employees across the nation.”); Supreme Court Takes Up Janus v. AFSCME, Buckeye Inst. for Public Pol’y Solutions (Sept. 28, 2017) (“We are pleased that the Supreme Court will take up this crucial case . . . We are confident that Mr. Janus will prevail.”).

[69] Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, SourceWatch.org (last visited Dec. 4, 2018).