Partisan Justice

How Campaign Money Politicizes Judicial Decisionmaking in Election Cases

by Joanna Shepherd and Michael S. Kang

Summary

The upward spiral of big money fundraising and aggressive politics in state judicial elections pressures judges to become partisan actors who favor their own party in deciding election disputes. Bush v. Gore is by far the most famous of this kind of election case, but state courts decide many similar cases every year, regularly determining who wields power at the state and local level. State judges are under enormous political pressure to join in party-based fundraising and campaign networks to survive what has become a fiercely competitive electoral environment. Analyzing a new dataset of cases from 2005 to 2014, this study finds that judicial decisions are systematically biased by these types of campaign finance and re-election influences to help their party’s candidates win office and favor their party’s interests in election disputes.

Principal Findings

- Judges favor litigants from their own party in head-to-head cases.

- Campaign finance exacerbates partisan behavior.

- Judges are less likely to be partisan when they no longer need to run for office.

- The problem of partisan decision making is arguably getting worse over time.

As election challenges have increased dramatically since Bush v. Gore, courts now are asked more than ever to resolve these highly charged partisan battles. Understanding how judges decide these election disputes is important in its own right — these increasingly common election cases regularly settle partisan fights over election rules and go a long way in deciding which party’s candidate wins office. Just as importantly, though, understanding election cases reveals deeper problems with judicial partisanship in today’s new era of judicial politics. The major parties and other powerful political actors now routinely spend millions of dollars in state court elections because state judges decide a full spectrum of cases ranging from environmental and consumer protections to criminal law to reproductive and voting rights. The increasing cost of elections escalates pressures on judges to rule in ways that help them to raise campaign funds from their partisan sponsors and protect their re-election interests.

The study finds that judicial partisanship is significantly responsive to political considerations that have grown more important in today’s judicial politics. Judicial partisanship in election cases increases, and elected judges become more likely to favor their own party, as party campaign-finance contributions increase. This influence of campaign money largely disappears for lame-duck judges without re-election to worry about.

This study is based on work by a team of independent researchers from Emory University School of Law that is forthcoming in Stanford Law Review. With support from the American Constitution Society, the researchers collected and coded data from over 500 election cases from all 50 states from 2005 to 2014. The data included over 2,500 votes from more than 400 judges in state supreme courts.

Introduction

State Courts Touch Our Lives in Countless Ways

State courts decide over 100 million cases each year. Many of these decisions shape lives in the most powerful and intimate ways imaginable…

State courts are responsible for more than 90 percent of the cases handled by the American judicial system each year. The federal courts and especially the U.S. Supreme Court capture the vast majority of the (admittedly small) amount of attention the media pay to legal and constitutional issues, but it is state courts and their decisions that most people encounter in their daily lives.

The U.S. Supreme Court decides about 100 cases per year. State courts decide over 100 million cases each year. Many of these decisions shape lives in the most powerful and intimate ways imaginable: child custody, divorce, consumer disputes and criminal prosecutions. Other state court cases determine public policy on issues ranging from civil and human rights to environmental protection. And since Bush v. Gore, state courts have overseen a dramatic rise in election cases deciding specific electoral disputes over results and procedures.

…increasingly, state court judges are called upon to act as referees in the political system.

So increasingly, state court judges are called upon to act as referees in the political system. Elections decide who exercises power in our system of democracy, but when candidates and parties dispute election outcomes and procedures in state and local elections, state judges are called on to wade into the political fray and resolve these contentious, highly-charged controversies.

Do judges decide cases, particularly politically sensitive ones, based on their partisan loyalties or the legal merits of the cases?

State Courts Decide Election Cases Similar to Bush v. Gore Every Year

In deciding the 2000 presidential election, the Supreme Court case Bush v. Gore presented a fundamental question for judges and our legal system: Do judges decide cases, particularly politically sensitive ones, based on their partisan loyalties or the legal merits of the cases? In a state court system where nine out of ten judges themselves are elected (thus placing them in a system in which judges often must themselves raise money, assemble political coalitions and turn out voters in order to remain in office), this question is more important than ever.

Since Bush v. Gore, election litigation has grown dramatically…

Although Bush v. Gore was the most momentous election case we can imagine, each year state courts decide many similar cases in which partisan election disputes hang in the balance. How judges decide these cases often determines who wins and loses elections, and thus who is in a position to set government policy and exercise political power at the state and local level. Since Bush v. Gore, election litigation has grown dramatically as candidates have become increasingly comfortable going to court to contest election outcomes. As a result, state courts, including many consisting of judges who are themselves selected through partisan elections, play a progressively greater role in deciding who wins office.

The Growing Importance of Money and Politics in Judicial Selection

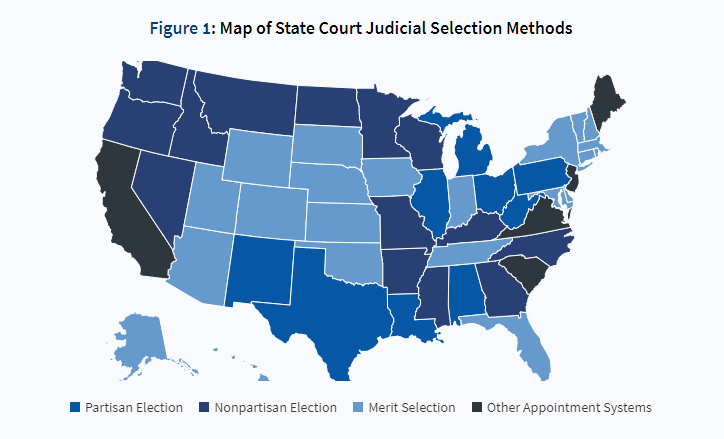

Given the importance of state courts in deciding state and federal elections, it is important to understand how state judges are selected. States divide roughly among four different systems of judicial selection and retention:

- partisan elections;

- nonpartisan elections;

- gubernatorial appointments; and

- merit plans.

In almost every state, the process by which judges are selected and retained in office exposes them to political pressures. Even when judges are selected by appointment or merit plans, they typically face “retention” elections in which incumbent judges run unopposed and must win majority approval to retain office. Only three states grant their supreme court judges permanent tenure without re-election or reappointment by the political branches as a condition to remaining in office. As a result, almost all state supreme court justices must please some combination of voters and politicians who will determine whether they keep their judicial seats.

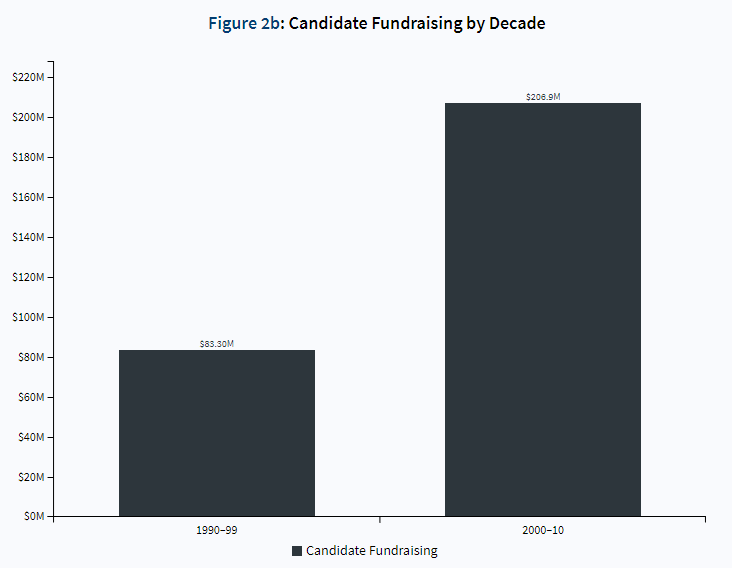

Since 2000, state supreme court races have undergone a revolution. Once characterized as sleepy affairs in which little money was raised or spent and active campaigning was rare, supreme court elections now are highly-politicized and contentious contests, with millions of dollars routinely raised and spent by and on behalf of the candidates. While incumbents rarely lost reelection bids in the 1980s, incumbents’ loss rate rivaled those of congressional and state legislative incumbents by the 2000s. The new style of aggressive judicial campaigning has been fueled by a flood of campaign contributions. State supreme court candidates raised less than $6 million total in the 1989–1990 election cycle, but in three of the last six election cycles, candidates raised more than $45 million.

Indeed, throughout the 1990s, only $83.3 million was contributed to state supreme court candidates; in contrast, candidates raised $206.9 million between 2000–2009.

The current system of state judicial selection thus requires judges to serve as neutral referees over their state’s political contests, while at the same time requiring them to take the playing field as partisan contestants. This report investigates how their party loyalty plays an important part in judicial decisionmaking in the most political cases and how campaign finance and re-election pressures make things worse. A more detailed discussion of the methodology used in this report can be found in a forthcoming article by the same authors in the Stanford Law Review.1

Impact

Judicial Voting in Election Cases

Ideological and Partisan Voting

Earlier attempts to empirically measure partisan voting confronted a vexing methodological problem. It is nearly impossible to disentangle partisanship from simple ideology in almost every case of judicial decisionmaking. Given that parties organize along ideological lines, partisan affiliation of a judge on one hand, and his or her judicial ideology on the other hand, are closely linked and difficult to disentangle from one another. Democratic judges tend to decide cases differently than Republican judges, but given the different ideological philosophies of the major parties, the partisan split between judges may simply be a legitimate ideological disagreement, rather than one motivated by partisan loyalty, perhaps particularly so for cases with high political stakes.

Cases dealing with voting rights, such as the dozens of cases on the constitutionality of voter identification laws that have been litigated over the past 10 years, illustrate this difficulty. Republican judges demonstrated a strong tendency to uphold such laws, and Democratic judges a corresponding tendency to strike them down. Many observers of the election process point out that strict voter identification laws favor Republican electoral interests, while reducing barriers to voting tends to favor Democrats. But are these trends in judicial decisionmaking the product of legitimate differences in legal ideology or illegitimate partisan interests? It is very difficult to say with certainty which is the case.

What Election Cases Teach Us About Judicial Partisanship

The kinds of election cases2 that are the subject of this study provide a unique opportunity to study judicial partisanship. Analyzing election disputes over contested election results and procedures, as opposed to ideologically charged cases over voting rights or campaign finance, solve the usual methodological challenge and isolate the partisan motivation of judges. The election cases in this analysis usually present relatively rare and present arcane questions of law, typically litigated by an election candidate. They arise from a legal question in a specific election, many involving the counting of ballots, or the technical eligibility of a candidate for a particular race, or something similar.

…election cases present judges with a clean, immediate opportunity to help their party, or hurt the other major party, usually with few or no complicated considerations of law that might play out in unforeseen ways in the future.

As a result, there is no ideologically conservative or liberal position on the merits of most of these questions as there is for other types of cases. Perhaps most importantly, no resolution of this type of case is even likely to advantage one major party above the other party over the long run. For instance, a decision to include a candidate as an eligible resident in a given election may help a judge’s party in that instance, but it may just as easily hurt the judge’s party the next time the question comes up. The short run partisan payoff in the current election is, however, typically quite clear: the winner of the case is more likely to win the election. The temptation for judges in these cases is therefore to help their party by voting either for the party’s candidate or against the opposing candidate.

Take, for instance, the issues at stake in the Bush v. Gore litigation. At the state level, these were picayune questions involving interpretation of obscure provisions of Florida state election code which had not arisen in the past and in which the parties had little stake beyond their impact on the 2000 election. But, of course, the stakes involved in the outcome of the particular case before the court literally could not have been higher. As a result, election cases tend to be very important in their short-term political effect but are otherwise unimportant legal issues with little foreseeable partisan advantage one way or the other over the long term. For this reason, election cases present judges with a clean, immediate opportunity to help their party, or hurt the other major party, usually with few or no complicated considerations of law that might play out in unforeseen ways in the future.

This risk of partisanship in election cases has worried election law scholars throughout the Bush v. Gore litigation and certainly ever since. The torrent of outrage over Bush v. Gore flowed from the widely-held perception that, depending on one’s partisan orientation, either the Republican-appointed majority of the U.S. Supreme Court, or the Democratic-appointed majority of the Florida Supreme Court, decided those cases in 2000 out of a desire to help their party’s presidential candidate, rather than fidelity to the law.

Although these concerns are intuitive, there has been very little systematic study of the parties’ campaign contributions and other campaign finance activity in judicial elections. The only empirical study of the role of party support on judges explored the relationship between judicial decisionmaking and contributions from a party coalition that includes both the judge’s political party and allied interest groups. The study found that contributions from both political parties and interest groups are associated with judicial voting in the preferred ideological direction of the relevant party coalition.3

Analysis

Data

Encoded Data from 2005–14:

2,500 Votes, 500 Judges, 400 cases, 50 States

This study explores whether partisan loyalty influences state court judges deciding election law cases. This report’s analysis of whether political party and party contributions are related to how judges decide election cases is based upon data from several different sources. First, a team of independent researchers from Emory University School of Law collected and coded data on over 2,500 votes in election cases from all 50 states from 2005 to 2014. The data included votes in over 400 cases and from more than 500 judges in state supreme courts.

The researchers coded whether each judge, sitting as a member of a multi-judge appellate panel, cast a partisan vote for the litigant/election candidate representing the interests of the judge’s political party. The researchers also coded details of each election case including the issue in the case, the geographic basis of the contested election, the litigants in the case, and the voting of other judges in each case. Additionally, the researchers collected data on each judge including their political party, the method by which they were selected for the court, and the date of their next reelection or reappointment. These data were merged with data on campaign contributions from the National Institute on Money in State Politics.

Methodology

The analysis tests the relationship between political party, campaign contributions, and partisan loyalty in election cases. The dependent variable is a vote either for a judge’s own party or against the judge’s opposing party in election cases. In cases involving a litigant/contested election candidate from the same party as the judge, the dependent variable takes a value of 1 when the judge votes for the candidate from the same party. In cases not involving a litigant/contested election candidate from the same party but involving a litigant/contested election candidate from the opposing party (i.e. a Democratic contested election candidate when the judge is Republican), the dependent variable takes a value of 1 when the judge votes against the opposing-party candidate. For example, in a case involving a Democratic candidate contesting the election results with claims that the absentee ballots are invalid, where a Republican judge votes to affirm the election results (voting against the Democratic candidate) the dependent variable would take a value of 1.

The two measures of political party support are the political party affiliation of the judge and the contributions from political parties and allied interest groups.4 All estimations also include a series of judge-level, case-level, and state-level variables to control for other factors that might be related to judges’ voting.

Results

Principal Findings

… judges affiliated with both parties tend to cast partisan votes in election cases.

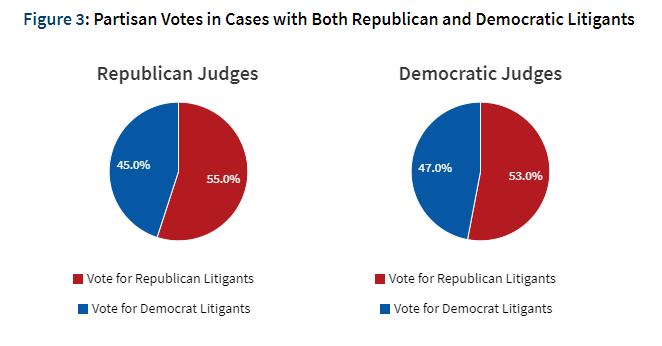

Judges Favor Litigants from Their Own Party in Head-to-Head Cases

As an initial matter, the study uses the raw data to compute the propensity of judges to vote for litigants from their own parties in cases pitting a litigant from the Democratic Party against a litigant from a Republican Party. Figure 3 reports the results. It shows that in these cases, compared to Republican judges, Democratic judges are more likely to favor Democratic litigants. Similarly, compared to Democratic judges, Republican judges are more likely to favor Republican litigants. Thus, in cases that determine whether a Republican or Democrat wins an election, the data suggest that judges affiliated with both parties tend to cast partisan votes in election cases.

- Republican judges systematically favor their own party in election cases by a statistically significantly greater margin

- Republican judges are 36 to 38 percent more likely to cast partisan votes in election cases.

Although Figure 3 suggests that judges affiliated with both parties may engage in partisan voting, this analysis also determines whether one party is more likely to cast partisan votes than the other. To make the comparison, this study uses Democratic judges as the baseline and determines how Republican judges’ voting compares to this baseline.

The results reveal that Republican judges systematically favor their own party in election cases by a statistically significantly greater margin, controlling for other things, than do Democratic judges. Specifically, the estimations indicate that Republican judges are 36 to 38 percent more likely to cast partisan votes in election cases. Notably, partisan favoritism by Republican judges is not dependent on selection method. In other words, Republican judges favor their party in election cases whether they are selected to the bench by election or political appointment. This result underscores the fact that all selection methods encourage judges to curry favor with whomever controls their retention, whether it is the electorate or partisan officeholders.

But why might judges affiliated with the Republican Party exhibit a greater tendency to vote in favor of their party? This study assumes that there is no significant difference in the personal characteristics, professionalism or commitment to the rule of law of judges affiliated with the Democratic or Republican parties. Although the authors are further studying the data, a Republican advantage in the underlying legal merits of the cases is not readily apparent in the dataset and does not easily explain why Republicans would display greater partisanship than Democrats. Furthermore, the analysis found that the nonpartisan and independent judges voted evenly in favor of Democratic and Republican litigants, and if anything displayed a tendency to vote in favor of Democrats, not Republicans.

Campaign Finance Exacerbates Partisan Behavior

The nature of the Republican Party’s system of campaign finance and donor networks may explain why judges affiliated with the party are more responsive to partisan incentives and thus more likely to favor the party in their decisions. The Republican Party appears to be more effective than the Democratic Party at using judicial campaign finance to affect state supreme court decisions across a whole spectrum of issues beyond election cases.5 Republicans may do so by using campaign finance to better select candidates with strong party loyalty on the front end or to better incentivize judges on the back end, but whatever the means, campaign finance contributions bear a greater relationship with partisan loyalty for Republican elected judges in these cases than Democrats.6

Figure 4 reports the average contributions of political parties and allied interest groups to state supreme court candidates in our data. The average is computed only for judges receiving contributions from each group, and the number in parentheses in each cell reports the number of judicial candidates receiving contributions from each group. The campaign contributions from various interest groups are aggregated to create a measure of contributions from conservative interest groups7 and contributions from liberal interest groups.8 The data capture only direct contributions from the party coalitions themselves to the judicial candidates’ campaigns; they do not capture independent expenditures and issue advocacy. As a result, the data certainly underestimate the total spending by political parties and party-allied groups by a significant margin.

As a result, the larger the amount of campaign contributions Republican judges facing elections received from the Republican Party and from party-allied interest groups—general business groups, financial/real estate business groups, insurance companies, medical groups, and conservative single-issue groups—the greater amount of partisan favoritism they demonstrated. The results reveal that while Republican judges remain systematically more likely to cast partisan votes, contributions from conservative sources increase the likelihood that a Republican judge will vote either for her own party or against the opposing party. In contrast, contributions from liberal sources decrease the likelihood that a Republican judge will vote for her own party or against the opposing party. Figure 5 reveals the marginal impact of each additional $10,000 contribution from conservative and liberal sources on Republican judges’ likelihood of voting for their own party or against the opposing party.

Figure 3 previously reported that Republican judges receive approximately $109,000 on average from the Republican party and $221,000 from conservative allied groups. The estimation reflected in Figure 5 reveals that, for an average judge in this data, an additional $10,000 in contributions is associated with a 3 percent increase in the likelihood of partisan voting. The relationship between liberal contributions and partisan voting is much smaller in magnitude; for every $10,000 contribution from liberal sources, Republican judges are approximately 0.8 to 0.9 percent less likely to cast a partisan vote.

The Increasing Importance of Campaign Finance in Judicial Elections

With the increasing competitiveness and expense of judicial elections, political party support has become critically important. Parties help candidates raise money, finance advertising campaigns, formulate campaign strategy, and mobilize supportive voters.9 Parties not only contribute money directly to judicial candidates affiliated with them, but just as importantly, they connect their candidates to sympathetic interest groups to help them succeed in judicial campaign finance.

The increasing cost of judicial campaigns has made it extremely difficult for candidates to win elections without substantial funding. In the 2013-2014 election cycle, the top campaign fundraiser prevailed in over 90 of contested state Supreme Court races.10 Indeed, many judges lament the intense pressure to appeal to contributors.

Mirroring the increases in direct campaign contributions, the last decade has also seen a dramatic increase in spending on television advertising in judicial races. Candidates, political parties, and interest groups have realized that, although television advertising is extremely expensive, it also is very effective in increasing name recognition and support for favored candidates, or alternatively, attacking their opponents. In the 2011–2012 election cycle, $33.7 million was spent on television advertising, making it the costliest election cycle for TV spending in judicial elections.11

In return, the parties expect officeholders, including judges, to loyally support the party line. Parties, as one political scientist puts it, must “persuade, cajole, or coerce fellow party members to vote consistently with the designated party position.”12 As a result, an empirical relationship between party money and partisan behavior by all officeholders, including judges, should not be surprising.

Judges Are Less Likely to Be Partisan When They No Longer Need to Run for Office

The analysis also finds that partisan voting is stronger among judges facing future election pressure. Thirty-seven states have mandatory retirement laws that compel judges to retire sometime between age seventy and seventy-five. By examining the voting of judges in their last term before mandatory retirement, the analysis can determine whether elected judges continue to cast partisan votes when they no longer need to attract campaign funds or advertising support. The results in Figure 6 reveal that, for judges in their last term before mandatory retirement, the relationship between campaign contributions and partisan voting disappears; for lame duck incumbents who are vacating their seats, conservative contributions actually decrease the likelihood of Republican judges casting partisan votes, and liberal contributions seem to have no effect. These results suggest that the need to raise future campaign funds is an important factor in judges’ partisan voting.

The Problem of Partisan Decision Making is Arguably Getting Worse Over Time

This study also analyzed election cases from the State Supreme Court Data Archive for all 50 state supreme courts from 1995 to 1998. Because of the limited time span of the earlier data, these earlier election cases included only 200 individual judge votes and only 78 votes for judges with campaign contribution data. Nevertheless, the results from this limited earlier sample confirm our findings here: compared to Democratic judges, Republican judges were more likely to vote either for their own party or against the opposing party in election cases. However, as shown in Figure 6 the coefficients on Republican party affiliation are smaller in the earlier data, suggesting that Republican judges were less likely to cast partisan votes in the 1990s, before the explosion of spending on state supreme court elections over the past 15 years.

Conclusion

Today’s state court elections are more intensely politicized than ever, and rising campaign spending increases pressures on elected judges to promote their parties’ interests in state court. It is no surprise then that party favoritism and party campaign finance plays a major factor in how state judges decide the growing number of election disputes litigated in state court. This study provides the first systematic evidence of the hidden influence of raw partisanship and party campaign finance on judicial decisionmaking in these election disputes. Even more troubling, there is little reason to believe that partisanship influences judges only in election cases. If judges are influenced, consciously or not, by party loyalty in election cases, they are likely tempted to do so in other types of cases as well, even if it is methodologically difficult to prove the role partisanship plays. This study likely exposes just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

In response to this fundamental threat to fair and impartial courts, reformers have advocated, among other things, public financing of state judicial campaigns; term limits for state judges; and various merit selection, judicial evaluation, and disciplinary systems. This study empirically confirms the underlying suspicions about judicial partisanship and bolster the case for judicial selection reform.

Attribution

About the Authors

About the American Constitution Society

The American Constitution Society for Law & Policy (ACS), founded in 2001 and one of the nation’s leading progressive legal organizations, is a rapidly growing network of lawyers, law students, scholars, judges, policymakers and other concerned individuals. ACS embraces the progress our nation has made toward full embodiment of the Constitution’s core values and believes that law can and should be a force for improving the lives of all people. ACS is revitalizing and transforming legal and policy debates in classrooms, courtrooms, legislatures and the media, and we are building a diverse and dynamic network of progressives committed to justice. By bringing together powerful, relevant ideas and passionate, talented people, ACS makes a difference in the constitutional, legal and public policy debates that shape our democracy. For more information about the organization or to locate one of the more than 200 lawyer and law student chapters in 48 states, please visit acslaw.org. All expressions of opinion in this report are those of the author. ACS takes no position on specific legal or policy initiatives.

Endnotes

The upward spiral of big money fundraising and aggressive politics in state judicial elections pressures judges to become partisan actors who favor their own party in deciding election disputes. Bush v. Gore is by far the most famous of this kind of election case, but state courts decide many similar cases every year, regularly determining who wields power at the state and local level. State judges are under enormous political pressure to join in party-based fundraising and campaign networks to survive what has become a fiercely competitive electoral environment. Analyzing a new dataset of cases from 2005 to 2014, this study finds that judicial decisions are systematically biased by these types of campaign finance and re-election influences to help their party’s candidates win office and favor their party’s interests in election disputes.