May 26, 2022

Getting Front and Center to Confront Prejudice

Director, Starn, O’Toole, Marcus & Fisher and Former Attorney General of Hawaii

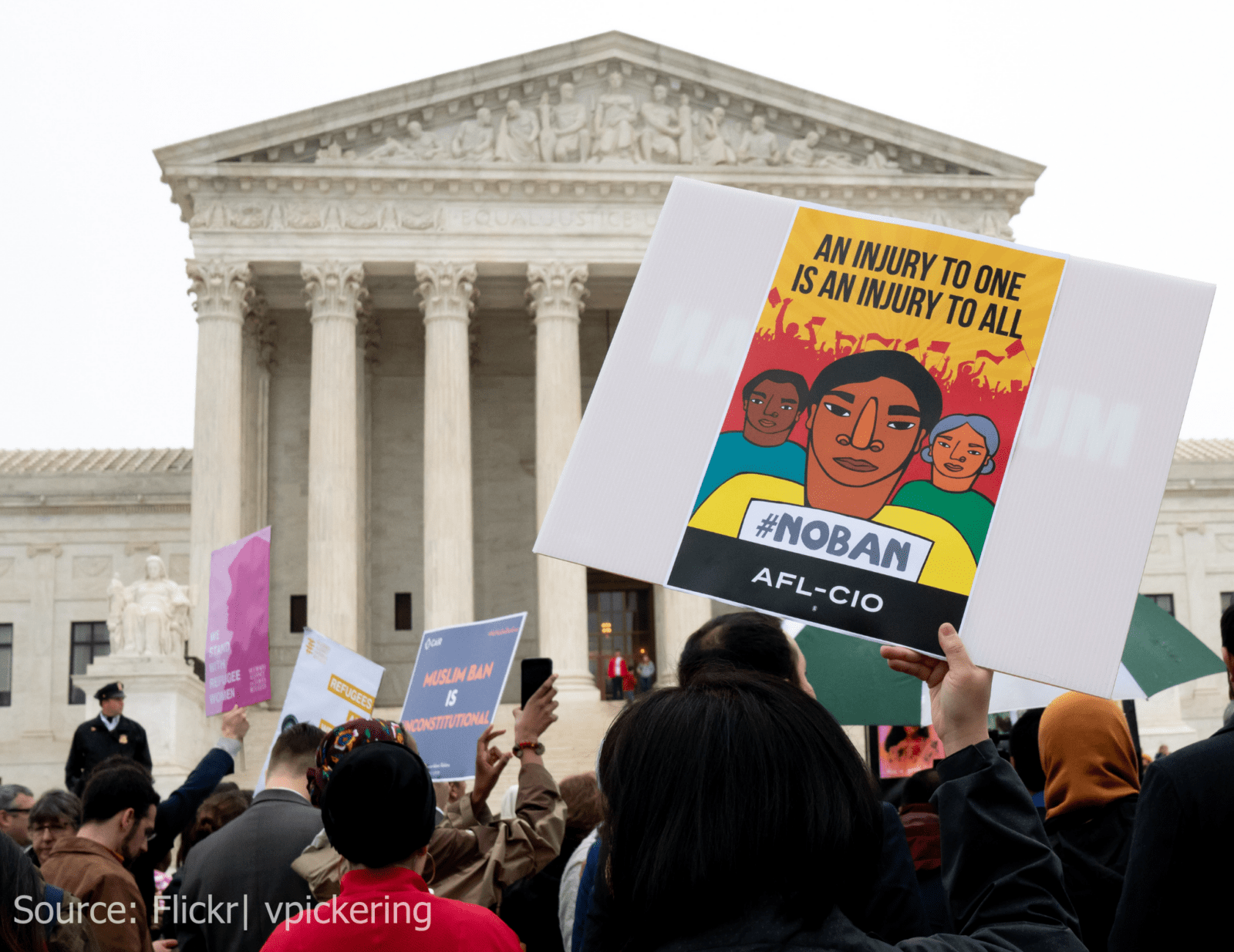

Travel Ban Rally in front of the Supreme Court as Trump v Hawaii is argued inside on 4/25/18

This is the third piece in an eight-month long blog series aimed at highlighting state attorneys general and their work. Upcoming blogs will feature writings from former and current state attorneys general and their staffs.

At the height of President Trump’s Muslim ban controversy, when lower courts deciding Hawaii v. Trump were consistently ruling that the ban was either blatantly unconstitutional or illegal or both, this comment showed up on the Hawaii Attorney General’s Facebook page:

“Get back in your corner, Hawaii.”

I was the Hawaii Attorney General at the time. My staff proposed the following reply:

“Nobody puts Hawaii in a corner.”

It was tempting. I said no, partly because I wasn’t sure millennials would know the Dirty Dancing reference, but also because this was our official government account and I wanted to maintain a certain decorum. Our otherwise snappy and perfect comeback to an anonymous troll remained an inside joke until today.

I knew very well what staying in the corner meant. Even though I was born in Seattle with all the rights and privileges of a U.S. citizen, I was still the son of Chinese immigrants who had learned English as a second language, left their homes and families, and came to America in hopes that their future kids (my sister and I) could have a better life. The knowledge of all that parental sacrifice ingrained in me early the responsibility to be a “model minority” – work hard, excel, and don’t call attention to yourself. “The nail that sticks up gets struck down” was a constant and even comforting mantra. I dumbed down my verbal answers in class to not look too smart. I was careful not to offend others with political statements and, due to how I was raised, I even looked down on those who did. In college, I never once marched in or participated at a political event. Same goes for law school.

Historically, Americans of Asian descent have faced serious forms of prejudice. In the late 19th century, the Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese immigrants from entering the country. During World War II, on February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 went into effect from the U.S. government. Its stated purpose was to provide “every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense material, national-defense premises, and national defense utilities.” The result of Executive Order 9066 was the imprisonment of more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans, many of whom were citizens. Yet, no case of espionage or sabotage by a Japanese-American was ever recorded during World War II. Though some brave individuals spoke up in outrage to these unjust laws – including Fred Korematsu, whose case against the United States, Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), led to the U.S. Supreme Court upholding the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 – most did not.

State Attorneys General Can Check the Federal Government

On January 27, 2017, I watched from my geographically remote corner of the country while President Trump’s initial Muslim ban took effect. Trump made good on his campaign statements that “Islam hates us,” that people who practiced the Muslim religion were terrorists, and that he would order a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the country when he took office. As a result, air passengers in flight were told they would not be allowed to enter the U.S. when they arrived. Green card holders from the banned Muslim-majority nations heard the same. Refugees who had waited years to escape horrific circumstances in their own countries were immediately barred from entering the country, a ban that has remained largely unchanged to this day. The weekend the ban took effect, protesters marched in airports around the country, including 5,000 miles away from Washington, D.C. in Honolulu’s typically non-controversial, tourist-friendly airport, where hundreds of people, many of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) descent, gathered to speak out.

My immediate reaction was that this was a dangerous step down a fast, slippery slope towards internment camps based upon blatant, unconstitutional discrimination or worse. Several of my state attorney general colleagues at the time held similar concerns or had other serious misgivings towards the President’s action. Within days, lawsuits brought by states including Hawaii against the Muslim ban were filed in federal courts.

In our federal system, states have a unique capability and responsibility to serve as a check on the federal government. States, through their attorneys general, can successfully claim standing and assert themselves into controversies in ways individuals or private organizations cannot. Under the parens patriae doctrine, a state attorney general may assert claims on behalf of the state’s residents and to act as the legal protector of those who are unable to protect themselves. A state may also sue the federal government when the state’s own wide-ranging sovereign interests, including the interests of its public agencies and institutions, come under threat. In Hawaii v. Trump, courts at all levels expressly accepted or did not reject Hawaii’s assertion that the travel ban, enforced upon public university students and faculty from Muslim-majority countries, would diminish the university experience and injure the State. The successful assertion of standing on behalf of a state unlocks the door to the federal courthouse and the potential for a federal judge to issue an order which carries a nationwide effect. In this way, individual state attorneys general possess an extraordinary superpower which they can use to challenge and halt federal government actions. Recent history has shown that state attorneys general can wield this power for good and just causes or for not-so-good purposes. That is why the various races for state attorney general are so important in states that elect their attorney general, and the races for governor are important in states in which the governor appoints the attorney general.

The Fight Against the Muslim Travel Ban

From his courtroom in Honolulu, Hawaii federal judge Derrick K. Watson, an individual of Pacific Islander descent, granted Hawaii’s motion to block the Muslim ban and ordered that it take effect nationwide. This caused then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions to publicly complain that there was an “activist AG” (apparently referring to me) in Hawaii and that it was too bad a judge on an “island in the middle of the Pacific” could unilaterally halt the President’s executive action. (In response to Sessions, my office tweeted a picture of the Hawaii state constitution, a social media post I did allow). In his ruling that the Muslim ban violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Judge Watson wrote this statement that struck me as especially poignant: “The Court will not crawl into a corner, pull the shutters down, and pretend it has not seen what it has.”

In a 5-4 decision, 585 U.S. __ (2018) – after the U.S. Government issued what Trump described as a “watered-down version” of his original Muslim ban, and then issued a third iteration which diluted, at least on paper, the focus on Muslim-majority nations – the Supreme Court in 2018 overturned the lower courts’ decisions and upheld the ban. The majority opinion expressly referred to the 1944 Korematsu decision as “gravely wrong” and overruled it, though in her dissent, Justice Sotomayer wrote that the Trump decision “redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one ‘gravely wrong’ decision with another.”

I have been asked on occasion whether it was difficult to go from being a self-proclaimed member of the “model minority,” who throughout my life had watched most controversies from the “corner,” to becoming the Hawaii Attorney General who sued the President of the United States and took it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Frankly, the decision to sue the President took less time than deciding what to say in response to the social media posts which followed. To me, the Muslim ban represented dark, fearful, irrational hatred. It was brazenly unconstitutional and illegal. It was a step backwards from progressive ideals. It was not a path or direction I wanted my country to take. It stood against values of diversity, acceptance and inclusion which make Hawaii, and the rest of America, so special. As a state attorney general, bringing a lawsuit to uphold and respect the U.S. Constitution and its laws was required by the oath I made when I took office. As an Asian American, it was an opportunity to be front and center in the ongoing fight to confront prejudice in America.

Doug Chin is a Director at Starn, O’Toole, Marcus & Fisher. He served as Hawaii’s Attorney General from 2015-2018 and was the first Hawaii Attorney General to chair the Conference of Western Attorneys General, and the first to serve on the Executive Committee of the National Association of Attorneys General. He serves on the Board of Directors of the Leadership Center for Attorney General Studies.

Equality and Liberty, Immigration, Racial Justice, Roles of State Attorneys General, State Attorneys General