Skewed Justice

Citizens United, Television Advertising and State Supreme Court Justices’ Decisions in Criminal Cases

by Joanna Shepherd and Michael S. Kang

Summary

The explosion in spending on television attack advertisements in state supreme court elections accelerated by the Citizens United decision has made courts less likely to rule in favor of defendants in criminal appeals. State supreme court justices, already the targets of sensationalist ads labeling them “soft on crime,” are under increasing pressure to allow electoral politics to influence their decisions, even when fundamental rights are at stake.

Citizens United (which removed regulatory barriers to corporate electioneering) has fundamentally changed the politics of state judicial elections. Outside interest groups, often with high-stakes economic interests or political causes before the courts, now routinely pour millions of dollars into state supreme court elections. These powerful interests understand the important role that state supreme courts play in American government, and seek to elect justices who will rule as they prefer on priority issues such as environmental and consumer protections, marriage equality, reproductive choice and voting rights. Although their economic and political priorities are not necessarily criminal justice policy, these sophisticated groups understand that “soft on crime” attack ads are often the best means of removing from office justices they oppose.

This study’s two principal findings:

The more TV ads aired during state supreme court judicial elections in a state, the less likely justices are to vote in favor of criminal defendants. As the number of airings increases, the marginal effect of an increase in TV ads grows. In a state with 10,000 ads, a doubling of airings is associated on average with an 8 percent increase in justices’ voting against a criminal defendant’s appeal.

Justices in states whose bans on corporate and union spending on elections were struck down by Citizens United were less likely to vote in favor of criminal defendants than they were before the decision. Citizens United changed campaign finance most significantly in 23 of the states where there were prohibitions on corporate and union electioneering prior to the decision. In these states, the removal of those prohibitions after Citizens United is associated with, on average, a 7 percent decrease in justices’ voting in favor of criminal defendants.

The study is based on the work of a team of independent researchers from the Emory University School of Law. With support from the American Constitution Society, the researchers collected and coded data from over 3,000 criminal appeals decided in state supreme courts in 32 states and examined published opinions from 2008 to 2013. State supreme courts are multi-judge bodies that decide appeals collectively by majority vote; the researchers coded individual votes from over 470 justices in these cases. These coded cases were merged with data from the Brennan Center for Justice reporting the number of TV ads aired during each judicial election from 2008 to 2013. A complete explanation of this study’s methodology is below.

The findings from this study have several important implications. Not only do they confirm the influence of campaign spending on judicial decision making, they also show that this influence extends to a wide range of cases beyond the primary policy interests of the contributors themselves. Even more troubling, the findings reveal that the influence of money has spread from civil cases to criminal cases, in which the fundamental rights of all Americans can be at stake.

Background

Judicial Elections and Campaign Finance

State courts play a vital role in American democracy

State courts handle more than 90 percent of the United States’ judicial business. Although vastly more attention is paid to the U.S. Supreme Court, it decides fewer than 100 cases each year, compared with over 100 million cases arising annually in the state courts. State courts handle the cases that are most likely to directly touch people’s lives: child custody, divorce, consumer disputes and criminal prosecutions.

In addition, just as the U.S. Supreme Court decides cases that have important and wide-ranging public policy implications, so too do the state supreme courts, deciding cases arising from state laws and constitutional provisions involving civil and human rights, environmental protections and the criminal justice system. State supreme courts decide who can get married to whom, who can vote, who can drink clean water and breath clean air, who the police can detain, search and arrest and who goes to jail and for how long.

State supreme courts play an especially important role with respect to criminal law. Prosecutions in state courts account for almost 94 percent of felony convictions, including an overwhelming majority of those for serious, violent crimes1. For example, approximately 98 percent of murder cases and 99 percent of rape cases are prosecuted in the state courts. In deciding these cases, state courts, and especially supreme courts, not only try to ensure that the guilty are punished and innocent go free, but also determine the scope of fundamental constitutional rights for everyone. These criminal cases raise issues implicating rights such as privacy, freedom from unreasonable search and seizures and confronting one’s accusers. Everyone, not just criminal defendants, has a stake in how these cases are decided, because a state supreme court’s decision to limit or narrowly interpret a defendant’s rights under a state constitution similarly restricts those rights for everyone in that state.

Elections play an important role in how state court judges are selected

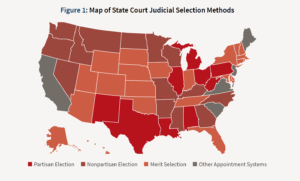

Given the vital role that state courts play in American democracy, the process by which states select their judges also is extremely important. Almost 90 percent of state appellate court judges must regularly be re-elected by voters. Today, there are four different principal systems of judicial selection and retention:

- partisan elections

- nonpartisan elections

- gubernatorial appointment

- merit selection plans

In the selection of judges to their highest courts, 9 states use partisan elections and 13 states use nonpartisan elections.2 In 28 states, the governor or legislature initially appoints judges to the highest court, with 21 of those states using some form of merit plan. For the retention of judges on the state’s highest court, 6 states use partisan elections and 14 states use nonpartisan elections. Eighteen states hold retention elections to determine whether those judges remain in office beyond their initial term, and the incumbent judges run unopposed and must win majority approval for retention. Nine states rely on reappointment by the governor, legislature or a judicial nominating committee. Only three states grant their highest court judges permanent tenure.

The growing importance of money in judicial elections

The last 20 years have marked a new era of contentious politics and exploding spending in the once sleepy world of judicial elections. Before the 1990s, judicial elections were low-key affairs, attracting little campaign spending and often less attention from voters. The very few exceptions to this pattern, including two aggressive campaigns in the 1980s that used the death penalty as a wedge issue to oust justices in California and Tennessee, were viewed as outliers by most observers.

But beginning in the 1990s, and accelerating in almost every election cycle since, judicial elections have become more competitive and contentious, and campaign spending on these elections has skyrocketed. Incumbent judges almost never lost their reelection bids during the 1980s, but by 2000 their loss rates had risen higher than those of congressional and state legislative incumbents.3

The harder-edged, more aggressive campaigns of this new era were fueled by a flood of campaign contributions. In the 1989–90 campaign cycle, state supreme court candidates raised less than $6 million, but by the 2007–08 cycle, candidates raised over $45 million for their campaigns.4

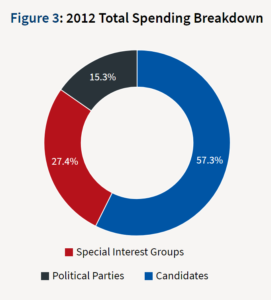

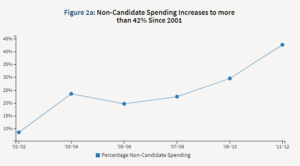

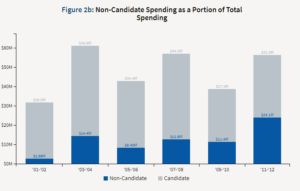

Just as notable as the explosion in the amount of spending on state supreme court elections are the twin transformations in how this money is raised and how it is spent. Increasingly, the money in judicial elections flows not to the campaigns of the candidates, but rather to independent expenditure groups, which while they have an interest in who wins elections and thus becomes a judge deciding cases, have no direct connection to the campaigns of the candidates. For example, in the 2011–12 campaign cycle independent expenditures accounted for 43 percent or $24.1 million of the $56.4 million spent in judicial elections during the cycle.5

A recent spur for this explosive growth in independent expenditure spending in state judicial races was the U.S. Supreme court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. Citizens United was the most important and publicly controversial campaign finance case decided by the U. S. Supreme Court in nearly 40 years. It overruled a half a century’s worth of federal law by declaring unconstitutional federal prohibitions on corporate electioneering. The Court’s decision provoked unprecedented outcry for a campaign finance case and clearly struck a public nerve. The biggest impact of Citizens United continues to be the larger deregulation of independent expenditures by outside groups that it has ushered in.

A recent spur for this explosive growth in independent expenditure spending in state judicial races was the U.S. Supreme court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. Citizens United was the most important and publicly controversial campaign finance case decided by the U. S. Supreme Court in nearly 40 years. It overruled a half a century’s worth of federal law by declaring unconstitutional federal prohibitions on corporate electioneering. The Court’s decision provoked unprecedented outcry for a campaign finance case and clearly struck a public nerve. The biggest impact of Citizens United continues to be the larger deregulation of independent expenditures by outside groups that it has ushered in.

Citizens United contributed to dramatic increases in independent expenditures at the federal level by outside groups such as Super PACs, 501(c) and 527 organizations. According to the nonpartisan research organization Open Secrets, outside spending on independent expenditures and electioneering communications surged suddenly to roughly $87 million in the 2010 federal elections, the same year Citizens United was decided. This total represented a nearly sixfold increase from the previous off-year federal election in 2006. By the 2012 presidential election year, outside spending mushroomed even further to an unprecedented $439 million, a more than fourfold increase over the previous presidential election year.

Citizens United contributed to dramatic increases in independent expenditures at the federal level by outside groups such as Super PACs, 501(c) and 527 organizations. According to the nonpartisan research organization Open Secrets, outside spending on independent expenditures and electioneering communications surged suddenly to roughly $87 million in the 2010 federal elections, the same year Citizens United was decided. This total represented a nearly sixfold increase from the previous off-year federal election in 2006. By the 2012 presidential election year, outside spending mushroomed even further to an unprecedented $439 million, a more than fourfold increase over the previous presidential election year.

Independent expenditures and the new politics of judicial elections

After Citizens United, independent expenditures and electioneering in state judicial elections have increased just as dramatically. Independent expenditures in these state judicial races had already accelerated even before Citizens United. For instance, whereas only $2.7 million of independent expenditures was spent on state supreme court elections in the 2001–02 election cycle, by the 2007–08 election cycle, over $12.8 million was spent. Available data indicates that this politicization has increased even further since Citizens United; the 2011–12 election cycle saw over $24 million of independent expenditures.6

The increase in independent expenditures and electioneering by outside groups has only accelerated in judicial elections since Citizens United. Interest groups spent over $15.4 million on state supreme court races in the 2011–12 cycle, accounting for more than 27 percent of the total.7 This spending represents an increase of over 50 percent compared to election cycle with the next highest outside group spending. The majority of money spent by the biggest contributors now goes toward independent expenditures rather than candidate contributions; 97 percent of the dollars spent by the top 10 spenders in 2011–12 were independent expenditures.

The flood of independent expenditures after Citizens United has not merely made judicial elections more expensive. It has transformed how they are conducted (largely via TV ads), altered their tone (by making harsh attacks much more common) and changed the substance of the issues addressed (criminal justice issues, often in the form of “soft on crime” attacks, are now commonplace). In 2012, an estimated $33.7 million dollars was spent on TV ads in state supreme court elections, with unprecedented levels of independent expenditures and electioneering by outside groups in particular.8 As is often the case, outside groups delivered messages via these ads that were more harshly negative than those put forth by the candidates and their campaigns. Forty-four percent of the ads sponsored by outside groups were attack ads. In contrast, only 2 percent of candidate ads and 11 percent of party-sponsored ads were negative in tone.9

Effects

The Influence of Money in Judicial Elections

Other Empirical Studies

A large body of empirical evidence now demonstrates that money often manages to buy what it wants in judicial elections. Increases in television advertising and independent expenditures by outside groups in particular, raise important concerns about their relationship to judicial decision making and independence. The authors of this study have written extensively about the worrisome relationship between campaign contributions and judicial decision making. In a previous study, Shepherd found that contributions from various interest groups are associated with increases in the probability that judges will vote in favor of the litigants whom those interest groups favor.10 In another study, the authors specifically analyzed contributions from business groups and found that campaign contributions from business groups to state supreme court justices were correlated with judicial decisions favorable to business interests, at least in states with partisan judicial elections.11Shepherd later found that the relationship between business contributions and judges’ voting was stronger in the period from 2010 to 2012, compared to 1995 to 1998.12 In a separate article, the authors also found that political party contributions and independent expenditures in support of state supreme court justices were correlated with judicial decisions in favor of the position preferred by the party across a wide range of legal issues.13

Public and Judicial Opinion

Moreover, 76 percent of voters believe that campaign contributions have at least some influence on judges’ decisions and almost 90 percent of voters believe that with campaign contributions, interest groups are trying to use the courts to shape policy.14 Even worse, judges generally agree that money matters in judicial decision making. Forty-six percent of judges believe that campaign contributions have at least “a little influence” on their decisions, and 56 percent believe “judges should be prohibited from presiding over and ruling in cases when one of the sides has given money to their campaign.”15 Moreover, 80 percent of judges believe that with campaign contributions, interest groups are trying to use the courts to shape policy.16

One jurist who has taken note of the role political forces have come to play in judicial selection is U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. In Woodward v. Alabama, a 2013 case arising from an Alabama law giving elected trial court judges the power to set aside sentencing determinations made by juries, including the imposition of the death penalty, Justice Sotomayor wrote a powerful dissent from the Court’s decision not to hear the appeal. Citing a study by the Equal Justice Initiative,17which found that 92 percent of the sentences overridden by Alabama judges set aside life sentences in favor of the death penalty and that the proportion of death sentences imposed by judicial override is elevated in election years, Justice Sotomayor wrote that the only explanation for the functioning of the Alabama system “that is supported by empirical evidence is one that, in my view, casts a cloud of illegitimacy over the criminal justice system: Alabama judges, who are elected in partisan proceedings, appear to have succumbed to electoral pressures.”18

How Money in Elections Influences Judicial Decisions: A Note on Causation

These same concerns regarding rapidly growing levels of money in judicial elections and political pressure on judges also arise for the recent surge in independent expenditures by outside groups and the television advertising that they fund. The increasing cost of campaigning for state supreme court might affect the politics of judicial elections and judicial decisionmaking in at least two obvious, important—and troubling—ways.

First, outside groups can get what they want by paying for television advertising that helps sympathetic judges win office and thereby shape the ideological composition of the state judiciary. Outside groups can first determine which candidates are most likely to decide cases as the groups prefer and which candidates they want to oppose. These outside groups can then fund television advertising campaigns that help their favored candidates, and attack their opponents, thus helping favored candidates win and retain judicial office over candidates less sympathetic to the group’s interests. In this way, independent expenditures and television advertising help decide judicial elections and shape the judiciary in the direction that outside groups prefer.

Second, less obviously, judicial candidates may foresee the importance of such independent expenditures and TV attacks ads and thus consciously or unconsciously bias their decisions in order to insulate themselves from such attacks. Judicial candidates may be tempted to lean toward the preferred positions of wealthy outside groups, either to draw their support or at least avoid their opposition in subsequent elections. What is more, judicial candidates may want to do what they can to decide cases in ways that do not leave them vulnerable to campaign attacks through negative TV ads.

Why Independent Expenditure Groups Often Feature Criminal Justice Issues in Their Ads

This study explores the effect of increasing independent expenditures following Citizens United on judicial decision making by examining criminal appeals. Previous empirical studies on judicial selection and criminology establish that criminal cases are particularly effective in motivating voters and more likely to be considered by judges with electoral considerations in mind.19 Independent expenditures are more negative overall than advertisements by candidates, who prefer not to “go negative” if they can avoid doing so. Candidates for judicial office are frequently concerned about appearing aggressively negative, wishing instead to convey an image of “judicial temperament” in their campaigns. Thus, the best means of paying for a sensationalist attack advertisement involving a violent, bloody fact pattern may be an independent expenditure by an outside group not directly connected to the benefitting candidate.

Because this combination of funding and electioneering techniques is so effective, it should be particularly worrisome to those concerned about the influence that money in judicial elections can have on judicial decision making. These concerns are particularly relevant in appeals arising from criminal cases, in which the liberty (and in capital cases, the life) of the defendant, as well as the constitutional rights of all residents of the state in question, are at stake.

Both judicial candidates and outside groups are well aware of the power of attack advertisements that portray judges as “soft on crime.” For example, during a 2004 West Virginia Supreme Court election, an outside group called And for the Sake of the Kids, which was funded by Massey Coal Company CEO Don Blankenship ran an TV ad alleging that an incumbent justice voted to release a “child rapist” and then “agreed to let this convicted child rapist work as a janitor in a West Virginia school.” Similarly, an ad in a 2012 Louisiana Supreme Court race claimed that a candidate had “suspended the sentence of a cocaine dealer, of a man who killed a state trooper, two more drug dealers, and over half the sentence of a child rapist.” Fear-provoking advertisements such as these, funded by outside groups without public accountability, can swing an election and put judges on notice that their judicial careers may be at stake each time they consider voting in favor of a defendant in a criminal case.

Attack: Candidate Bridget McCormack “fought to protect sexual predators” |

Attack: Candidate Bill O’Neill “sympathetic to rapists” |

Attack: “When he was a district attorney, Incumbent Justice David Prosser covered up” |

| State: Michigan, Sponsor: State Republican Party | State: Ohio, Sponsor: State Republican Party | State: Wisconsin |

Results

Skewed Justice: Empirical Analysis

This study finds that increases in television campaign advertising, often funded by independent expenditures, are associated with justices voting against criminal defendants in ways that call into greater question the fundamental fairness of the criminal justice system.

The more TV ads aired during state supreme court judicial elections in a state, the less likely justices are on average to vote in favor of criminal defendants.

Justices in states whose bans on corporate and union spending on elections until they were struck down by Citizens United were less likely on average to vote in favor of criminal defendants than they were before the decision.

Data

To explore whether the increase in TV ads has influenced state supreme court justices’ rulings against criminal defendants, this study compiled data from several different sources. First, a team of independent researchers from Emory University School of Law collected and coded data from almost 3,100 criminal appeals decided in state supreme courts. Because justices’ votes are likely to become fodder for future TV attack ads in only the most heinous cases, the researchers examined only cases involving certain violent crimes tracked by the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program: murder, robbery, violent aggravated assault, and rape and other sex crimes. The cases were randomly selected from state supreme court published opinions from 2008 to 2013 from 32 states.20 The researchers coded the individual votes from over 470 justices in each of these cases.21 All coding went through a two-step quality control process; ultimately, over 25 percent of the cases were coded by at least 2 researchers to confirm reliability.

The researchers coded whether the justice, sitting as a member of a multi-judge appellate panel, voted in favor of the criminal defendant on appeal. Following other data on judicial decisions, a vote in favor of a defendant is defined as any vote that improves the defendant’s position—whether it is overturning any part of a criminal conviction or reducing a defendant’s sentence. In addition, the researchers coded data on the offense for which the defendant was convicted, the number of victims involved in the crime and whether any victims were juveniles. The researchers also collected data on each state’s ban on corporate and union independent expenditures prior to Citizens United, data on individual judge characteristics, and data about state judicial selection and retention methods.

These data were merged with data from the Brennan Center for Justice, “Buying Time” project. Since 2000, the Brennan Center has collected all available televised state supreme court campaign ads that were aired in states holding supreme court elections. This data on TV ad airings are calculated and prepared by Kantar Media/CMAG, which captures satellite data in the nation’s largest media markets. The authors compiled the Brennan Center’s data measuring the number of TV ads aired during each judicial election from 2008 to 2013.

Methodology

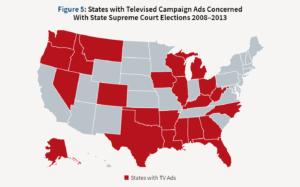

The analysis tests whether the threat of future TV attack ads influences justices to cast more “tough-on-crime” votes. It measures the threat of future attack ads in two different ways. First, it uses the number of televised campaign ads that aired in the most recent supreme court election in each state; this measure assumes that recent airings determine justices’ estimates of the likelihood of future attack ads. Figure 5 reports states in which TV campaign ads concerned with state supreme court elections aired in the years 2008–13. The average number of TV campaign ads aired in each state per year was 3,650; the minimum was 30 and the maximum was 17,830.

The study’s second measure of the threat of future attack ads is the nonexistence or removal of a ban on corporate and union independent expenditures. Prior to the Citizens Uniteddecision, 23 states had bans on such spending. As most TV ads sponsored by interest groups are funded by independent expenditures, the availability of such spending can dramatically increase the possibility of future TV attack ads. Figure 5 identifies which states had a ban on independent expenditures from either corporations or both unions and corporations at the time of the Citizens United decision. Citizens United also may have increased independent expenditures even further by opening the door to independent expenditure-only committees, known at the federal level as Super PACs, that can receive uncapped contributions from their donors.22

Control variables in the estimations include various case, judge and state characteristics that might also influence judicial voting. Case characteristics include the crime for which the defendant was convicted (murder, aggravated assault, rape, robbery), the number of victims, and whether any of the victims were children. It also includes a measure of the underlying strength of the case. This control variable is important because some cases are so strong (or weak) that justices will vote in favor of or against the criminal defendant regardless of their ideological predisposition or the influence of TV ads. To create a measure of case strength, we estimate how many of the justices hearing a case would be predicted to vote in favor of the defendant based on certain quantifiable case and state characteristics. The difference between this predicted number and the actual number of justices voting in favor of the defendant provides a measure of case strength—the more justices voting in favor of the defendant compared to the predicted number, the stronger the defendant’s case.

The study also takes into account the justices’ political party affiliation to control for the role of ideology on justices’ voting in criminal appeals. It includes indicators for retention method for state supreme court justices to measure whether the method of reelection or reappointment affects judicial voting. All estimations also include state and year fixed effects to capture systematic differences in the criminal appeals process across states and general trends in TV ads. The analysis estimates a series of ordinary probit models with t-statistics computed from standard errors clustered by case.

Results

The More TV Ads, The Fewer Votes in Favor of Defendants

The analyses reveal that TV ads are associated with justices casting fewer votes in favor of defendants in criminal appeals. The first analysis finds that the more TV ads aired during state supreme court judicial elections in the state, the less likely justices are to vote in favor of criminal defendants. The results are statistically significant across numerous estimations that alter the specification and include various combinations of control variables, ensuring robustness.

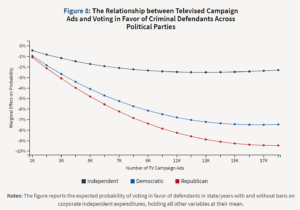

To illustrate the results in an intuitive way, Figure 7 shows the relationship between the number of TV ads aired and justices’ likelihood of voting in favor of criminal defendants. The figure reports, for different numbers of televised campaign ads, the expected change in the justices’ probability of voting in favor of the criminal defendant if ads increased by 100 percent, holding all other variables at their mean value. That is, the figure shows that in a state that aired only 2,000 ads, a doubling of airings would be expected to decrease justices’ voting in favor of defendants by 2 percent, or change a justice’s vote in 2 percent of cases. However, as the number of airings increases, the marginal effect of an increase in TV ads grows. In a state with 10,000 ads, a doubling of airings would change a justice’s vote in 8 percent of cases.

The analysis also explores whether the relationship between televised campaign ads and judges’ likelihood of voting in favor of defendants vary across political party. As a baseline, Republican justices are, on average, slightly less likely to vote in favor of defendants than other justices; in this sample, Republican justices voted in favor of the defendant in 27 percent of cases but Democratic justices voted in favor of defendants in 31 percent of cases. However, the analysis indicates that TV ads exacerbate this difference. Figure 4 shows that, although campaign ads are related to decreases in voting in favor of defendants across all parties, the relationship is more pronounced for Republican justices. Even starting from different baselines, the relationship between campaign ads and judicial voting is stronger for Republicans than either Democrats or Independents.

Justices Less Likely to Vote in Favor of Defendants After Citizens United

The analysis also explores whether the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United had any impact on justices’ votes in criminal appeals. The Court’s decision immediately was followed by a dramatic increase in both the actual number of TV ads aired during judicial elections and the threat of future TV ads. However, Citizens United changed campaign finance most significantly in the 23 states that had bans on corporate or union independent expenditures prior to the ruling; 27 states had no such ban and thus were not as affected by the Citizens United decision. The analysis empirically exploits this variation across states and the resulting differential effect of the decision to isolate the impact of corporate and union independent expenditures in judicial elections on justices’ votes in criminal appeals.

The results from this analysis indicate that unlimited corporate and union independent expenditures are associated with a decrease in justices voting in favor of defendants. The results are statistically significant across different specifications and with different control variables. Unlimited independent spending is associated with, on average, a seven percent decrease in justices’ voting in favor of criminal defendants. That is, the results predict that, after Citizens United, justices would vote differently and against criminal defendants in 7 out of 100 cases.

Conclusion

In states with more advertising and perhaps more competitive electoral environments, elected judges are more likely to be electorally sensitive to being seen as “soft on crime” and therefore less sympathetic to criminal defendants when they decide criminal appeals. At the margin, whether consciously or unconsciously, they prefer to avoid a judicial vote in a criminal case that can be the basis for attack advertisements funded by independent expenditures.

Indeed, the analysis set forth above demonstrates that as television advertising in a state goes up, state’s judges are more likely to decide criminal appeals against criminal defendants. The analysis also demonstrates that Citizens United exacerbated the influence of money in judicial elections influence on judicial decision making. In the 23 states that had bans on corporate or union independent expenditures, Citizens United’s lifting of these bans is associated with a decrease in justices voting in favor of defendants.

These findings are likely to be only a preview of escalating trends in judicial campaign finance and elections. There has been only one presidential election cycle since Citizens United. Outside groups, whether funded by corporations, unions and wealthy individuals have only begun to professionalize their operations and will only grow more sophisticated in the years to come.

Attribution

About the Authors

![]()

Joanna Shepherd

Professor of Law, Emory Law School

Joanna Shepherd teaches Torts, Law and Economics, Analytical Methods for Lawyers, Statistics for Lawyers, and Legal and Economic Issues in Health Policy. Before joining Emory, Professor Shepherd was an assistant professor of economics at Clemson University. Much of Professor Shepherd’s research focuses on topics in law and economics, especially on empirical analyses of legal changes and legal institutions. She has published broadly in law reviews, legal journals, and economics journals. Professor Shepherd received a BBA from Baylor University and a PhD from Emory University.

![]()

Michael S. Kang

Professor of Law, Emory Law School

Michael S. Kang’s research focuses on issues of election law, voting and race, shareholder voting, and political science. His work has been published by the Yale Law Journal, NYU Law Review, and Michigan Law Review, among others. Professor Kang received his BA and JD from the University of Chicago, where he served as technical editor of the University of Chicago Law Review and graduated Order of the Coif. He received an MA from the University of Illinois and his PhD in government from Harvard University. After law school, Professor Kang clerked for Judge Michael S. Kanne of the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and worked in private practice at Ropes & Gray in Boston before joining the Emory Law faculty in 2004.

About the American Constitution Society

The American Constitution Society for Law & Policy (ACS), founded in 2001 and one of the nation’s leading progressive legal organizations, is a rapidly growing network of lawyers, law students, scholars, judges, policymakers and other concerned individuals. ACS embraces the progress our nation has made toward full embodiment of the Constitution’s core values and believes that law can and should be a force for improving the lives of all people. ACS is revitalizing and transforming legal and policy debates in classrooms, courtrooms, legislatures and the media, and we are building a diverse and dynamic network of progressives committed to justice. By bringing together powerful, relevant ideas and passionate, talented people, ACS makes a difference in the constitutional, legal and public policy debates that shape our democracy. For more information about the organization or to locate one of the more than 200 lawyer and law student chapters in 48 states, please visit acslaw.org. All expressions of opinion in this report are those of the author. ACS takes no position on specific legal or policy initiatives.

Endnotes

The explosion in spending on television attack advertisements in state supreme court elections accelerated by the Citizens United decision has made courts less likely to rule in favor of defendants in criminal appeals. State supreme court justices, already the targets of sensationalist ads labeling them “soft on crime,” are under increasing pressure to allow electoral politics to influence their decisions, even when fundamental rights are at stake.