May 11, 2018

What We Learned From Gina Haspel

Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Floersheimer Center for Constitutional Democracy, Yeshiva University Benjamin Cardozo School of Law

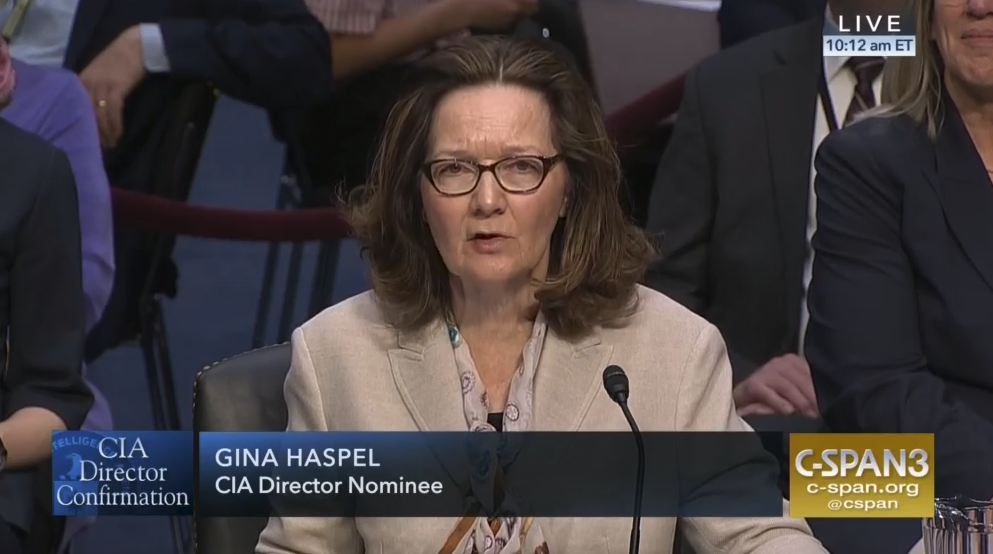

At Wednesday’s hearing before the Senate Intelligence Committee considering her nomination to be CIA Director, Gina Haspel talked a lot about “leadership lessons” – lessons not only reflecting the knowledge and experience she plainly has, but presumably the deeper insights and judgment one gains after trying and failing, as we all inevitably do, to do the right thing at the critical time. The great disappointment of Haspel’s testimony was in how evident it became that she seems to have learned the wrong ones.

Even before the Wednesday hearing, Haspel’s nomination was opposed by scores of retired military leaders, and an equal number of America’s ambassadors and diplomats; there are likewise many individuals in our intelligence community who cite the same reasons as Haspel’s opponents for thinking America should never go down the torture road again. Our torture program violated the law, endangered our troops, empowered terrorist recruiters, imperiled essential counterterrorism cooperation with our most stalwart allies, did lasting physical and psychological harm both to the prisoners we tortured and the men and women we demanded torture them, and compromised our most basic values as a country. As John McCain put it back it 2005: “"It's not about who they are. It's about who we are." These lessons were hard won indeed.

But Haspel declined repeatedly on Wednesday to condemn torture; to make clear she would refuse a presidential order to torture; to take responsibility for her own part in the program’s past or her own role in the destruction of video evidence of the program (videos she testified she never herself watched); to indicate that she thought, by 2007 or even now, that the program should have come to an end; or in any other way to acknowledge that the torture program was not the right thing for America to do. To the extent she offered Congress reassurance of any kind that she would stand against a return to policies past, it was a commitment that “under my leadership, CIA will not restart such a detention and interrogation program.” This is careful language, and woefully limited. For as became apparent during the hearing, the reason why Haspel has been willing to offer this much is because she thought the program was the wrong thing for the CIA to do – because, as she explained, the CIA lacked any relevant knowledge or experience in detention or interrogation at the time the program was created, and because she witnessed the steep price CIA agents involved in the program paid for their participation.

That the CIA had no experience in running a detention and interrogation program after the attacks of 2001 can hardly be doubted. Of course the CIA by then had a long (unattractive) history of training others in the brutal treatment of prisoners in decades past. But Haspel’s account yesterday echoes many other post-9/11 analyses of what the CIA had, by 2001, become. Neither she nor others there had relevant knowledge (much less insight) of their own about what such a program should involve. Of course, for many workers in many industries – from commercial airline pilots or mechanics to doctors or lawyers – being asked by a superior to take on a task one knows one is manifestly unqualified and unprepared to do might prompt a quite different response. For it is not as though the U.S. government as a whole lacked all experience with interrogation and detention on September 11, 2001. Quite the contrary. The CIA (and, in Thailand, though the details remain purposefully obscure, even Haspel herself) had to work actively to kick those who did have expertise (like FBI agent Ali Soufan) out of the interrogation booth. This is not stepping up, or leaning in. This is knowingly flying a plane or issuing a prescription without a license. The alternative view – that Haspel didn’t know what she didn’t know – is perhaps worse. For what is it that she doesn’t know she doesn’t know today?

As for the price CIA agents paid for their involvement in the program, there is likewise little reason to doubt that some paid something. While no fulltime CIA employee has faced any criminal punishment for any prisoner mistreatment – not for the men in whose deaths CIA is implicated, not for the man threatened with a power drill, not for the men locked in coffins or the prisoners left in their own excrement, not for the men subjected repeatedly to mock execution by drowning – jail time is not the only kind of price there is. There are administrative and professional sanctions, what can be the crushing expense of paying for legal representation when faced with even the prospect of liability, and emotional and psychological burdens that can be debilitating of themselves.

Yet while Haspel was clear in her testimony that she does not want to expose her own CIA colleagues to such harm again, she did not for a moment on Wednesday object – and it appears, never has – to the prospect that more expert or simply other agents acting in the name of the United States could well take such a project on, to whatever extent the law could be twisted to permit. She gave no indication she would take any steps to speak up or against the reintroduction of a torture program should some other U.S. agency undertake it. But the record is clear she would speak and act repeatedly to ensure that the video evidence documenting the CIA’s own role in such a program would never see the light of day. She learned the lesson that torture is damaging to people in the CIA. Not that it is damaging to America. Much less to the victims who suffer from it most. It is not clear what one might best call the lessons Haspel has learned from her deep experience in the CIA. But what they cannot reasonably be called are lessons in “leadership.”